Tack Faculty Lecture Series: A geological romp through the Commonwealth

Chuck Bailey gave a guided tour through a weird and wild Virginia, a place that not even the oldest members of the audience had seen.

Bailey spoke April 17 on “Finding Faults in Old Virginia,” the most recent installment in William & Mary’s Tack Faculty Lecture Series, to a full house in the Kimball Theatre in Williamsburg’s Merchant Square. Martha '78 and Carl Tack '78, benefactors of the series, were part of the near-capacity audience that looked to be a composite of current students, alumni, current and emeriti faculty and members of the community.

{{youtube:medium:left|X1-WS73jZyw, Tack Faculty Lecture Series: Finding Faults in Old Virginia}}

“Last year, we launched the Tack Faculty Lecture Series,” said William & Mary Provost Michael Halleran, who introduced Bailey. “Our intellectual energy as a university comes primarily from the creative work of our faculty as they conduct their research and lead students in their quest for new knowledge. And so we thought we shouldn’t hide our light under a bushel, but rather celebrate it.”

Professor of geology and chair of the department, Bailey is also a William & Mary alumnus, a member of the class of ’89. He is the first alumnus to present a Tack Lecture, which once each semester showcases the work of a scholar or researcher to the rest of the university as well as to the community at large. The next Tack Lecture will be Tuesday, Oct. 29 in the Kimball Theatre, when Deborah Steinberg, professor of marine science at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, will talk on “From Plankton to Planet.”

Bailey began his lecture by confessing that when he’s asked why he became a geologist, he often says it’s because he likes climbing mountains.

“That may not be the best answer to offer up, but think about it: Mountains are these very interesting environments and I’ve always liked the idea of being in mountains,” he said. “In mountains one is obviously confronted by the earth.”

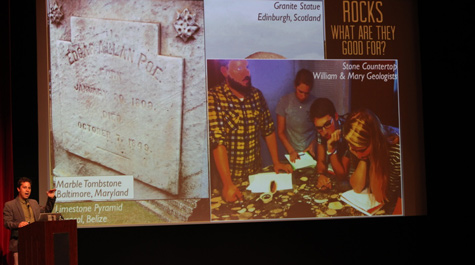

Bailey confronted his audience with the earth in various ways, presenting on the Kimball’s screen annotated views of processed rock that were essentially structural geology’s greatest hits. The audience was treated to an explanation of how blocks of the earth’s crust had been moved around in ways that are nearly incomprehensible for the layman. For example, the portion of earth that Virginians know as Goochland Courthouse is possibly the earliest “come-here,” moving down from New England some 300 million years before I 95 was constructed.

“Bits of Old Virginia originated in the northeast,” he said. “So think about that, the capital of the Confederacy has rocks that originated in Rhode Island and Massachusetts.”

Bailey showed photos and spoke of the contributions of various undergraduate research groups that he’s worked with over the years. The groups began to give themselves names, and accordingly, the audience heard of the contributions by the Alberene Dream Team, the Crozet Crackers and the Elkton Easter Bunnies, among others.

He augmented his presentation by distributing geologic “hors d’ oeuvres”—polished slices of mylonite, gneiss, hornfels, breccia, serpentinite and other Virginia rocks. As geology students, members of the Structure and Tectonics Research Group, served the morsels, Bailey deadpanned a caution, ostensibly from the university’s legal counsel, against trying to eat the hors d’ oeuvres. Instead of breaking a tooth, he encouraged the audience members to hold the geo-morsels in the light and admire them.

“You can hold one of these cubes up and you get the sense that these are pretty static,” Bailey told the crowd. “But these rocks that you have in front of you, the rocks that are so static right now actually have formed—and then of course been deformed—by a variety of processes that are actually very, very dynamic.”

He went on to show-and-tell about the various processes by which the earth bends, folds, squeezes and moves around portions of itself. Bailey also gave some insight on how he and his fellow geologists find out what the earth’s been up to in the last few hundred million years.

“How many of you have a light colored rock with little tubes?” he asked, displaying a similar sample on the screen. “You may notice that there are a variety of these little almost circular things. Well it turns out that those are actually burrows, burrows from a fossil organism that lived probably 520 million years ago or so.”

The creatures that made the burrows in untold gazillions throughout the sandy mud that eventually became the Commonwealth’s quartz sandstone are known as Skolithos worms, which Bailey explained are among the earliest remains of life found in Virginia. He called everyone’s attention to the Skolithos burrows on the screen. “They’re elliptical in shape,” he noted. “And my question is: How in the world did these become elliptical?”

The answer, he explained, is that the rock (and the worm tubes inside it) was deformed through tectonic forces. Bailey went on to discuss how geology students learn to use elliptical worm tubes and other features in rock samples to determine quantitatively how much the rock has been stretched or squeezed over time.

The processes still continue to mold the earth actively, Bailey said. He cited as an example the Aug. 23, 2011 earthquake, playing a clip with sound that recorded the reaction of the members of William & Mary’s Department of Geology as the 5.8 magnitude quake interrupted their departmental retreat.

Bailey gave a primer in earthquake mechanics and some sobering information: That 2011 quake that caused gargoyles to fall off the National Cathedral, closed the Washington Monument and interrupted learned discourse among William & Mary’s geologist was only a fair-to-middling event.

“It was probably one of the top 500 earthquakes of the year,” he said. Bailey compared the Virginia quake to the March 11 Japanese event, which all by itself released more energy than all the year’s magnitude 5 and magnitude 6 quakes added together.

He gave a rundown of the history of Commonwealth earthquakes and gave an outline of how the North Anna Power Station came to be built atop a fault, despite the warnings of geologists, including some from William & Mary. “It is a minor fault,” he added. “Let’s be clear about that.”

“Virginia is riddled with faults,” he said. “There are ancient faults and I think we can speak to the fact that there are active faults as well.”