Exposing Maggie Walker's life, one page at a time

{{youtube:medium|9ty3_KbZuLA}}

It has been four-and-a-half years since six William & Mary students made a startling discovery in the dark, dusty attic of St. Luke Hall in the Jackson Ward section of Richmond.

While the meticulous work of handling, cataloguing and preserving the contents of 31 boxes of documents and photos relating to the astounding life of Maggie Walker is not complete, tremendous progress has been made. 'Only' 10 boxes remain unexamined.

“Thus far, we have looked at 12,000 documents,” said William & Mary Adjunct Associate Professor Heather Huyck, whose class of Sharpe Fellows made the discovery in February 2009. “Our job is to put them in acid-free boxes, acid-free folders, page by page, handling them as gently as possible. Some are in superb condition, but others almost fall apart in your hands.”

Once that is done, the papers will be turned over to the National Park Service, which operates the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site in Richmond. However, a complete digital set will be housed on a W&M website, available to anyone, pending an agreement between Swem Library and the Stallings family of Richmond, which owns the building in which the papers were found.

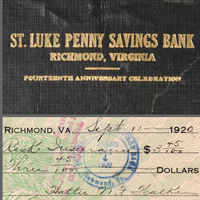

Born in 1864, while slavery was still in existence, Walker gained tremendous wealth through a variety of businesses. She was an insurance executive and head of the Independent Order of St. Luke, an organization dedicated to helping improve the lives of African Americans during the Jim Crow era. She was the first female bank president of any race to charter a bank in the United States, the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. That was 1903. During the Depression, it was one of the few banks nationally to receive FDIC certification.

She set up a department store, was the editor of the St. Luke Herald and was one of the few women to serve on the national board of the NAACP.

“She’s never received her just due, her full recognition,” Huyck said. “Not yet.”

Huyck credits Amy Clinger ’11 for having the “chutzpah” that led to the discovery. Clinger, five other students and St. Luke Hall owner Ron Stallings were in the building doing a video as part of a freshman seminar on the St. Luke Hall and its historical context that Huyck taught. Clinger persuaded Stallings to let the students climb the steep stairs leading to the attic.

There, under a pile of rubble, were boxes from the 1970s. Behind them were Walker papers from the 1920s and 30s that the group had been promised didn’t exist any more.

“(Clinger) had the sense and smarts and training from the class to get some sample documents so I could get some sense of what she was talking about” Huyck said. “As soon as I saw them, I knew it was a big deal.”

The only scholarly biography of Walker was based on public sources, not Walker’s perception of the life and times in which she lived and tried to make better.

“That’s where the collection becomes so important,” Huyck said. “It tells us things not available anywhere else. It’s her perspective and those of other people, other black women, on running a business, on each other and on the world.”

A diabetic and confined to a wheelchair following a fall down the stairs at her 28-room Richmond row house, Walker was a friend and confidant to some of the most influential people of her time.

“Here’s a woman who is functioning at the national level, talking to the head of the National Negro Bankers Association, developing that relationship, yet she, like the president of the United States at the time, is barely able to move,” Huyck said. “She and (Franklin Delano Roosevelt) are both wheelchair bound.

“We have letters from Maggie Walker where she’s staying in motels and hotels. She’s always writing ahead and saying ‘I need an extra room for someone to stay with me, and I need to be on the first floor because I can no longer climb steps.’”

The collection produced a letter to Walker from Mary McCleod Bethune, founder of Bethune-Cookman University and an adviser to FDR. She, another woman and four men were traveling from New York to Florida; Bethune asked Walker to secure for them a place to stay in Richmond and somewhere for the men to perform.

“They were trying to get to Richmond before night – this was the days before I-95,” Huyck explained. “I was curious about that. The men were to sing for their supper, or actually to get gasoline to go on with their journey.

“If you were an African-American in those days traveling was a difficult proposition.”

Huyck is proud to have made the Walker papers “a community project,” bringing together people to Swem Library who aren’t experts – like students and women from the Williamsburg NAACP and the National Negro Business and Professional Women’s Association – and providing them with training from experts like herself.

“I’d heard of Maggie Walker, but didn’t know that much about her,” said research volunteer Connie Cook-Hudson, peering out from under a facemask the cataloguers wear to protect the documents and themselves. “I can’t even express how wonderful a woman she was in her time, dealing with business matters and helping her community get established.

“All of these papers,” she continued, pointing to a folder in front of her, “it’s like you’re reading a book about a great woman!”

Although the collaboration has brought together people from different worlds, Huyck said it has also reinforced the notion that a divide still exists between the races.

Although the collaboration has brought together people from different worlds, Huyck said it has also reinforced the notion that a divide still exists between the races.

“We refer to that as the ‘turnip salad’ issue,” she said. “We discovered a reference to turnip salad and I said to them, ‘I don’t know about turnip salad, how do you make it?’ It turns out, they explained to me, there are two versions ... they all knew that. I then mentioned green bean casserole with mushroom soup, and onion rings on top. Most of the black women I know who have the same socio-economic background that I do don’t know about green bean and mushroom casserole. It’s an indication of how people don’t connect, even all these generations later.

“It’s what Maggie Walker fought for and tried to bring together, blacks and whites. Although she was what they called at the time a ‘Race Woman,’ dedicated to bettering the lives of African Americans, she also wanted people to come together. That we don’t know each other’s recipes – an indication that we haven’t shared meals together – is a tragic comment on all of us.”

Walker died in December 1934, but there are a few documents from after that date. How they got there is anyone’s guess.

“We don’t know a lot about the reaction (to her death),” Huyck said. “We know the black schools closed for her funeral. We know there was great suffering and sorrow. We’re still trying to get through the papers, but we have come to expect something interesting every day we work on this collection. It’s a doorway to another time and place."