A South African Founder in Williamsburg

The story and photos below are used with permission of history.org, Colonial Williamsburg's official history website.

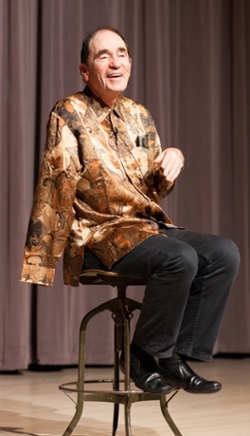

Albie Sachs considers himself the most privileged man in the world, comparing his opportunities to shape his nation's direction with America's founders.

"I'm in the civil rights movement, I'm in Philadelphia [at the Constitutional Convention], then later I'm [U.S. Supreme Court Justice] John Marshall."

Sachs, who rose from imprisoned freedom fighter to become a justice on South Africa's highest court, recounted his career in a talk on Sunday at Hennage Auditorium, co-sponsored by the Program in Comparative Legal Studies and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding at William & Mary Law School, the Reves Center for International Studies at the College of William & Mary, and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

The trajectory of his career is indeed spectacular. As a young lawyer he participated in the Defiance of Unjust Laws Campaign that fought South Africa's apartheid regime with civil  disobedience. He was imprisoned without charge, placed in solitary confinement and subject to sleep deprivation. In 1988, South African security agents attempted to kill him with a car bomb.

disobedience. He was imprisoned without charge, placed in solitary confinement and subject to sleep deprivation. In 1988, South African security agents attempted to kill him with a car bomb.

After the fall of apartheid, Sachs participated in the writing of a new constitution and was appointed to the nation's highest court by Nelson Mandela.

Sachs recounted the car bombing in detail, of losing consciousness, waking in a hospital and discovering that he had suffered the loss of his right arm and the sight in one eye. He recalled feeling "joyous and light" in the wake of the attack. After years of wondering, "Will they come for me today?" he had his answer. Instead of despair, he felt a new certainty in his commitment to the struggle. "As I recovered, so South Africa would recover."

Comrades in the African National Congress assured Sachs that the attack on him would be avenged. Its members shared an assumption that if "you captured someone, you did to them what they did to us." But Sachs fought that mentality. In exile, he wrote the code of conduct for the ANC, which he summarized as, "We don't torture. Full stop." There would be no revenge.

"If we get freedom, if we get democracy, that will be my soft vengeance," he said.

Sachs credited South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission with helping to heal many of apartheid's wounds. The commission conducted extensive hearings all over the country to document the experiences of people who were perpetrators, victims and witnesses of human rights abuses under apartheid.

Contrary to his initial misgivings, Sachs believes the fact that the business was conducted in public was essential to its success. Justice could not be reduced to cold logic. "You told your story just to tell your story." Sachs also described recognizing what he terms "a dialogical truth" that included multiple points of view. "We needed a common history," he said, in order to achieve a successful post-apartheid society that would bring all its people together.

So what of South Africa today? Has it achieved its goals?However, "for those people who say 'nothing has changed,' I'd say nothing has changed in their heads."

"Soft Vengeance," a documentary that chronicles Justice Sachs' life, premieres at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in Durham, N.C. April 5.

The Kimball Theatre is screening Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom through April 4.

Read Colonial Williamsburg's Q&A with Justice Sachs at history.org.