A bit of Civil War history survives … in an unlikely place

It was 1861, the early days of what would come to be called the Civil War. Benjamin Stoddert Ewell was professor of mathematics and president of the College of William & Mary, positions that didn’t mean very much as the institution had closed, just days after Virginia was accepted into the Confederate States of America.

President Ewell had become Major Ewell, the commander of an amalgamation of militia units called the Junior Guard. Robert E. Lee had a job for his fellow West Point graduate. The Federal forces were massing at Fort Monroe, down in Hampton. Lee needed to prevent Union troops from marching up the Peninsula and taking Richmond, the Confederate capital.

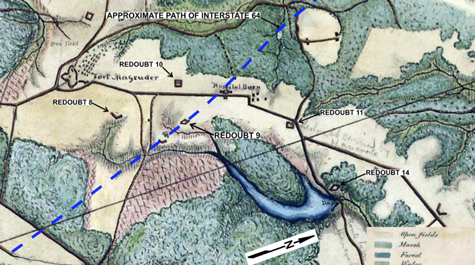

Lee directed Ewell to build a defensive line of earthworks across a four-mile long section of the Virginia Peninsula between the James and York rivers. Anchored by Fort Magruder, Ewell’s Williamsburg Line took shape as a string of 14 fortifications. When you take Interstate 64 between Williamsburg and Newport News, you pass right over Redoubt 9, one of the elements of the Williamsburg Line.

Redoubt 9 saw action — and occupation by both armies — during the war. Widening work by the Virginia Department of Transportation opened up an opportunity for VDOT and the William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research (WMCAR) to take another look at Redoubt 9 in 2016. Christopher Shephard, project archaeologist for WMCAR, issued a recent report on the Redoubt 9 dig. The report adds to the considerable historical and archaeological material surrounding the Peninsula Campaign.

“Williamsburg was a logical choice for building a string of fortifications. It occupies a narrow ridge between the York and James rivers and the Peninsula is further constricted just east of town by Queen’s and College creeks,” Shephard explained.

Redoubts are satellite fortifications associated with a larger fort. Redoubt 9’s “mother fort,” was Fort Magruder, he said. Fort Magruder was an extensive complex, incorporating living quarters for the troops, facilities for storing munitions and a reinforced area to protect the soldiers from shelling.

Redoubts are satellite fortifications associated with a larger fort. Redoubt 9’s “mother fort,” was Fort Magruder, he said. Fort Magruder was an extensive complex, incorporating living quarters for the troops, facilities for storing munitions and a reinforced area to protect the soldiers from shelling.

“Alone, however, Fort Magruder couldn’t cover all possible Union approaches up the Peninsula. That is why the Confederate Army constructed a series of 13 smaller redoubts between College Creek and Queen’s Creek,” Shephard explained. “These smaller redoubts, armed with field guns, were outposts where smaller groups of soldiers could theoretically expand the field of fire across the entire Peninsula.”

The 1862 Battle of Williamsburg was essentially the battle of the Williamsburg Line. Shephard summarizes the action in a report to VDOT: Confederate General Joseph Johnston’s forces were pursued from Yorktown by Brig. General George Stoneman’s cavalry and, as Shephard writes, “half of the Army of the Potomac.”

The retreating Confederates reached Williamsburg on May 4, and the pursuing Union forces began their attack on the Williamsburg Line the following day. One division tried and failed to take Fort Magruder. Union forces found Redoubts 11 and 14 unoccupied and just moved in.

Redoubt 9 was manned by the Sixth South Carolina. They fell under fire by Union troops under General Winfield Scott Hancock and were driven northwest towards the ravines that feed Queen’s Creek. “Soon the entire Williamsburg Line was in Union hands, a position that they occupied for the remainder of the War,” Shephard writes.

Redoubt 9 of the Williamsburg Line (there is a different Redoubt 9 on the Yorktown battlefield) lies between today’s I64 exits 238 and 242. The location was verified in a 2007 VDOT site examination. Shephard said that much of the site was disturbed during the 1960s construction of the interstate. But a fairly significant portion of Redoubt 9 escaped the worst of the heavy equipment earth-churn. It was between the east- and westbound lanes — in the median.

So, in 2016 Shephard led a WMCAR team to the median of an interstate to excavate the site of a Civil War battle. The archaeologists encountered something the men of the Sixth South Carolina never had to face in 1862— the summer beach traffic of I64.

“It was thrilling at times getting on and off the median of the interstate, especially during the height of the summer, but there are fairly comprehensive and stringent safety guidelines with which VDOT staff and contractors must comply — and they work well at preventing close calls,” Shephard said.

He added that WMCAR works frequently and closely with VDOT, and the standard arrangement is for the archaeological work to be scheduled well in advance of active road construction.

“It was interesting being able to see the traffic slow down and speed up throughout the day while we were working at the site,” he said. “Living in Richmond, I got a daily preview into how my commute home was going to be.”

One objective at Redoubt 9 was to examine the distribution of spent munitions at the site. As Shephard put it: “How do our interpretations of the data confirm, augment or complicate official descriptions of the battle by the Union and Confederate Armies?”

They used metal detector surveys, systematic test unit excavations and larger block excavations — quite thorough methods, especially considering WMCAR was working in a highway construction zone. They turned up a number of battle-related artifacts, but not what they were expecting.

“A combined total of ten fired bullets, eleven unfired bullets, one shrapnel fragment, and two metallic bullet cartridges were recovered from scattered locations across the site,” Shepard said. “Deposits of battle-related military artifacts are much more lightly manifested across the site than we expected—insufficient for interpreting patterns related to the flow of battle.”

Shephard said there are a couple of possible explanations for the scarcity of munitions uncovered at the dig. For one thing, it’s possible that the encounter between the Federals and the South Carolinian defenders of Redoubt 9 was extremely brief, with the majority of the fire taken and received in a running skirmish as the South Carolinians withdrew from the redoubt. Another possibility, he said, is that more intensive occupation and battle activity (and associated artifact deposits) were located in the areas immediately northeast and southwest of Redoubt 9, which were inadvertently disturbed by the construction below grade of the west- and east-bound lanes ofI64 in 1960s.

Shephard reported that the site yielded up artifacts of occupation, including buttons representing various Union units, dinnerware, a brick hearth that likely held a cookstove. The archaeologists even recovered a champagne bottle — empty, but intact.

Redoubt 9 was constructed by Confederates, but occupied by Union troops after the Battle of Williamsburg. It’s impossible to prove if Yanks or Rebs drank that champagne, but Shephard says there are plenty of artifacts — buttons, bayonet scabbards, ammunition, etc. — that are diagnostic to one army or another. And the archaeological tale of Redoubt 9 is mostly one of Union occupation.

“With the exception of one possible bullet we didn’t find anything that can be clearly linked to the Confederate Army,” he said. My interpretation is that after the Confederate Army built Redoubt 9, it was never manned—or rarely manned.”