Winston adds to historic Homecoming celebration

Warren Winston never shied away from being a ground-breaking student-athlete at William & Mary. He even rehearsed for the part.

Winston ‘72, the university’s first African-American scholarship athlete, helped break the color line at Richmond’s John Marshall High School. He and a friend bussed across town to what had been an all-white school.

He was a star athlete there, excelling in football, track and field and baseball, as well as in the classroom.

Recommended to the W&M coaching staff by an alumnus, the Winston family had already visited campus and attended a football game against West Virginia. Still, the senior was a bit unsure.

Winston’s decision to attend William & Mary was made — by his father, he laughingly remembered — when football coach Marv Levy paid his family a home visit.

“He was really impressive,” recalled Winston, who started at W&M in 1968. “Shortly after that visit from Coach Levy, it was pretty clear that William & Mary was where my dad wanted me to go.

“I welcomed the challenge, because I knew I’d be a pioneer. There were a lot of things going on in the 1960s: the Civil Rights movement, Vietnam War, the deaths of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. I thought [attending W&M] would be a very special opportunity to be a part of integrating a major college in Virginia.”

Winston will return to campus for this week’s Homecoming celebration, not as a spectator, but as a celebrity. He has agreed to be honorary team captain — wearing a newly minted jersey number 49 — and will make the coin toss Saturday before the Tribe takes on defending national champion James Madison.

Without doubt, many memories as a student will come rushing back.

{{youtube:medium|uDd85ygz3sg}}

Setting an example

When Winston arrived, there were only three African-American students residing on campus: Lynn Briley '71, Karen Ely '71 and Janet Brown Strafer '71. The university is commemorating the 50th anniversary of their presence on campus throughout 2017-18, including the dedication of alumni bricks in their name Saturday at 11 a.m. at the Alumni House’s Clarke Plaza.

Because the football team ate mandatory meals together and lived in facilities separate from the rest of the students, Winston said he knew Briley, Ely and Strafer were on campus, but didn’t see them until after the season. When they finally met, Winston said, “they took me under their wing, all three of them.”

“They were always very supportive, always gave me a lot of encouragement,” he said. “There was never any negativity; I didn’t hear the three of them question their decisions about being there. They seemed always very focused. All three were good students, and that was inspiring for me.”

At that point in his career, Winston said, he wasn’t very focused on academics.

“I was fairly immature when I first attended,” he said. “I didn’t understand that at the level we were at I needed to put in a lot more effort than I was putting in. The other part of my immaturity was that I figured I’d be playing professional football at some point, so the academic side didn’t matter as much. … Fortunately, my attitude changed after a couple of years.”

Lending integration support

Winston became close with a young new admissions officer, Sam Sadler B.A. '64, M.Ed. '71, who was tasked with recruiting black high school students.

Sadler, who served at the university from 1967 to 2008 and rose to become vice president for student affairs, asked Winston what he could do to entice more African-American athletes to attend W&M. Winston said he told him, “Recruit more females!”

“He was absolutely right,” Sadler said. “I turned to him on several occasions for advice. He was a remarkably poised, thoughtful, interesting young man. He was one of those people you take to the first time you meet him. I always found him to be a compelling individual. I think his record at W&M demonstrates that, not just on the field but also off of it."

Sadler’s influence on Winston was profound. He helped him achieve a graduate assistantship with the football staff so that he could complete his degree in sociology. One of the women Sadler successfully recruited was Rubenia Williams ’74 from I.C. Norcom High School in Portsmouth, Virginia. She and Winston were married in the Wren Chapel in 1978, have two adult children and a grandson who will celebrate with him this weekend.

Winston beamed with pride when he proclaimed that meeting his wife on campus was “the biggest thrill. I owe a lot of my happiness to her.”

While the university’s recruitment efforts brought in more African-American students, socialization was still difficult for Winston.

While the university’s recruitment efforts brought in more African-American students, socialization was still difficult for Winston.

“When I was there I could go days and weeks without seeing another black face on campus,” Winston said. “That was a challenge, but I had a very strong support system with my family.”

Winston once told his father that he was thinking about transferring. His father’s only response was, “I understand how you feel, but one thing troubles me: I never knew you were a quitter.”

“Those words were piercing,” Winston said. “A chill went through me. I knew right then that I was going to stay.”

That resolve led to what he called one of his proudest moments at the university. He joined with several other African-American students to establish the Black Student Organization.

“I’m very happy about that,” he said.

Finding support

One faculty member who stood out in Winston’s estimation was David Holmes, who retired in 2011 after nearly 50 years in the university’s religious studies department.

On a team flight to Philadelphia, where W&M would play Villanova, Winston suffered an attack of appendicitis. He was hospitalized there for a week and when he returned to campus a letter was awaiting him from Holmes, who was about to give Winston’s class an exam.

“He said, ‘I’m sorry to hear about your illness; you’ve missed a week of class, and I know you are behind. If there is something I can do to help you get ready for the exam — a one-on-one study session with me -- let’s do it.’

“I spent quite a lot of time with him getting caught up,” Winston said. “I was not only prepared for the exam, I did very well on it. He was the only professor I had who reached out and offered that kind of support, and I really appreciated it.”

Levy, the head coach who recruited him, left the school following Winston’s freshman year. His replacement was a corncob pipe-smoking swizzle stick of a former Tribe assistant named Lou Holtz. He spent three years at W&M before moving on to coach at several schools, including Notre Dame. He also coached the NFL’s New York Jets.

“After he left Notre Dame, I read a book about his experience there, and some of the stories made it clear that you either loved him or hated him,” Winston said. “I loved him. He was a great coach who came to my rescue many times.”

Holtz was sensitive about the racial climate at W&M. In one of his first speeches to the team, he pointed to Winston and declared that he intended to treat him “just as well or just as badly as anyone else on this team. I don’t want any issues as it relates to race.”

Holtz was a man of his word. One fraternity, many members of which were football players, had a Homecoming tradition in which they dressed in Confederate uniforms, marched around waving the Confederate flag and eventually stopped at the President’s house and posted a notice that they were “seceding” from the university.

Winston went to see Holtz.

“I told him, ‘If they chose to participate in the parade, then it would be my decision not to play in that game on Saturday,’” Winston recalled.

“He said, ‘Let me assure you, any teammate of yours that participates in that parade will not play in the game on Saturday. We want you to play.’ And that’s the way it went down.”

The decision, Holtz said when contacted recently, was easy.

“We don’t bring anything onto our football team except William & Mary,” he said, as if he still worked at the university. “If your actions hurt somebody else on the team, and they had nothing to do with it, that’s unfair and not the right thing to do.

“On the field or off it, Warren never did anything that disappointed me.”

Football to finance

A defensive back for most of his career, Winston said his best game came against Davidson College in 1971. Playing despite an injured leg the previous year at Davidson, Winston said he was “tested early and often, and I didn’t meet the challenge.”

“After the game, I was in tears because I was a very competitive player,” he recalled. “I carried that feeling with me for an entire year. The following year when they came to Williamsburg, I told myself that I was going to make them pay for that decision to go after me.”

Winston made a team-leading six tackles, broke up four passes and when W&M’s 40-14 victory had ended, Holtz not only praised him by name to the press but presented him with the game ball.

As a team, the highlight was the 1970 Tangerine Bowl in Orlando against Toledo. It was a reward for improving from a 3-7 record in 1969 to 5-6 and a comeback from three tough opening losses.

Winston’s goal of playing in the NFL didn’t materialize. He signed as a free agent with the Chicago Bears and went to training camp, “which lasted for a very short time.”

That led him to a graduate degree in social work from Virginia Commonwealth University, a brief teaching and coaching career at Bowie State University, and until his retirement two years ago, a 30-year career in financial services.

Winston admitted his role at the university featured unique problems other students didn’t face, but he walked away proud of the way he handled them.

“I knew that being the only black athlete that first year, that somebody had to open the door for others to have an opportunity,” he said. “I felt that I probably could do that.”

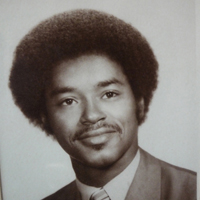

Sadler said that one look at the freshmen football team photo in the Colonial Echo speaks volumes about Winston’s character.

“He’s sitting on the front row, and he looks confident,” Sadler said. “He looks like he belongs there. That’s the way Warren always behaved. He carried himself in a way that said, ‘Hey, I belong here.’ And he most certainly did.”