A new president, a new ballgame

Conor Rooney ’18 takes a swing, breaking the silence with a wave of cheers. His base hit brings in the eighth run of the game.

Rooney and his teammates — Jackie Borman ’17 and Sarah DeVellis ’19 — haven’t missed a hit yet, but it’s not thanks to their sharp eyes and powerful swings. Instead, this ballgame relies on their out-of-the-park knowledge of such American figures as Jefferson, Nixon and Obama. This isn’t just an ordinary day at the ballpark.

This is Presidential Baseball.

A judicial start

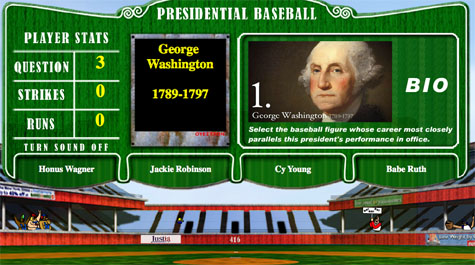

Founded by Paul Manna, Hyman Distinguished University Professor of Government at William & Mary and and chair of government, and Jerry Goldman, Professor Emeritus at Northwestern University, Presidential Baseball is a free online game that tests players’ knowledge of past presidents and baseball players. Each question presents a photo and a short bio of a former (or current) U.S. president and asks the user to choose which of four figures in baseball — from players to managers and umpires and others — is most similarly related.

“We think of the president as the face of the country, and people often describe baseball as the nation’s pastime,” said Manna. “So we thought this was a neat way to link up this figure who personally represents America to this game that through its history reflects a lot of aspects of American history.”

{{youtube:medium:left|fURV9Wj_z78, Clinton, Trump and Presidential Baseball}}

The game began as an offshoot of Goldman’s Oyez Project, a Supreme Court database dreamt up in the late ’80s while Goldman was at a Cubs game in Chicago. The original version was a series of complex HyperCard stacks made to resemble electronic baseball cards of Supreme Court Justices. That later morphed into a web-based game with multiple choice questions for each of the 108 Supreme Court justices called Oyez Baseball.

“The idea behind Oyez Baseball was to find a way for Americans to relate to the Supreme Court,” said Goldman. “Many of the justices are forgettable; they left no mark, and if they did those marks have been erased by time. But since Americans understand baseball, the great hope was that this would be a way to help them understand the work of the Supreme Court.”

Oyez Baseball launched in 2001 (though it has since been incorporated into the Oyez Project in a different form) and quickly drew publicity from national press and support from educators, students and fans across the country. A year later, Manna, a former student of Goldman’s who’d helped build Oyez Baseball and was just starting out as a professor at W&M, got the idea to take on a new branch of government.

Oyez Baseball launched in 2001 (though it has since been incorporated into the Oyez Project in a different form) and quickly drew publicity from national press and support from educators, students and fans across the country. A year later, Manna, a former student of Goldman’s who’d helped build Oyez Baseball and was just starting out as a professor at W&M, got the idea to take on a new branch of government.

“We had the infrastructure already built for the Supreme Court game so we really just needed to come up with the questions, and then we also added a few more bells and whistles,” said Manna.

A whole new ballgame

Presidential Baseball contains one question with four multiple choice answers for each person who has served as president. The player gets three chances (three strikes) to answer a question correctly. Unlike Oyez, each correct answer does not yield a run, but a single, double or triple base hit according to the level of difficulty of the question.

“A hanging curve ball is easy. A fastball down the middle is medium, and a slider is most difficult,” said Manna.

Each question, or at bat, tasks the player with the same thing: Select the baseball figure whose career most closely resembles this president’s performance in office.

“There is supposed to be a real connection,” said Manna. “So what we try to do is think about what the president is known for —accomplishments, scandals, whether they were the first to do something — and then we try to align those things with a baseball player who’s had similar accomplishments, failures or controversies.”

Some presidents, Manna said, were easy to pinpoint. Richard Nixon, for example, had a string of accomplishments during his presidency, including opening relations with China and creating the Environmental Protection Agency, but his successes were outshined by his scandals while in office. His baseball counterpart, Pete Rose, similarly had an outstanding career as the all-time hits leader before being banned from baseball for gambling.

Many presidents, however, were not as simple due to their largely uneventful presidencies, leading Manna and Goldman to get creative with certain similarities, such as pairing right-wing presidents with right-handed hitters.

“One of the points that we hoped to underscore with this game is that some presidents are great, some are horrible, but a lot of them are kind of so-so, which is like baseball,” he said. “There are very few true superstars in baseball; most of them are just okay. And we think that’s kind of reflected in the performance of presidents, too.”

Presidential future

These days, Manna continues to run the show with help from W&M students, updating the game as new presidents are elected and occasionally revisiting the answers of former presidents to include more contemporary players.

“I could recite a lot of the starting lineups from the late ’70s through the early ’90s,” Manna said. “But I just don’t keep track of contemporary players at that level of detail anymore. That’s where my students come in.”

Along with undergraduates like Rooney, Borman and DeVellis, Manna has already begun brainstorming potential baseball figures in anticipation of the Nov. 8 election.

“I think for Trump you’d have to find someone who is a polarizing figure — people either love him or they hate him,” Manna said. “Politics is also his second career, so you could also think of someone who is known in baseball but had some kind of notoriety before they played baseball. And then also maybe someone who is not shy about talking about their own abilities and knowledge, like Reggie Jackson.”

Borman cites Tim Tebow as a potential answer due to his shift from football player to baseball player,, while DeVellis suggests Alex Rodriguez, a controversial player with a reputation for being untruthful.

On the opposite side of the aisle, Manna and his students argue that Clinton could be compared to baseball figures who’ve either broken barriers — as she would do as the first female president — or who have had substantial, but not necessarily game-changing, careers on the field thus far, such as Juan Uribe or Johnny Damon.

But, Manna notes, without a presidency to evaluate for either of them, that answer could change by the next election.

“Whatever question we write in November we’ll have to rewrite four years from now after we see their track record,” Manna said.

To play Presidential Baseball, visit prezbaseball.org.