The Thomas Harriot Observatory opens for star-gazing

The transit of Venus is, at best, a twice-in-a-lifetime event. Transits come in pairs, eight years apart, and these pairs come more than 100 years apart. If you didn’t see the planet of love pass between the earth and the sun on June 5, you’ll have to wait until 2117 for the next chance.

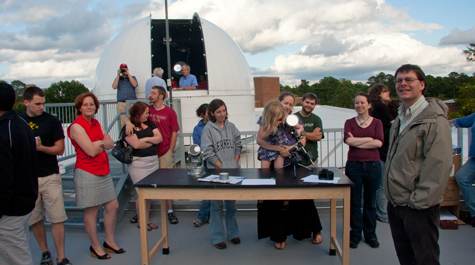

Bob Vold, like many astronomers, missed the 2004 transit of Venus because of clouds. On June 5, 2012—transit day—it was cloudy again. The weather forecast predicted the cloud cover might start to clear, encouragement enough for Vold to start calling and e-mailing. He had a brand new observatory to show off and there was no occasion better than the transit of Venus for a coming-out party.

Vold is a professor of applied science and also the director of William & Mary’s Thomas Harriot Observatory. The observatory was the last major component of the expansion and renovation of Small Hall. The new dome and its 14-inch computer-controlled telescope will give William & Mary much improved astronomical functionality.

More people will use the observatory than you might think. The physics department requires all its majors to complete a senior project or honors thesis. Vold says that usually two or three seniors each year pursue an astronomy project. “We haven’t had any the last couple of years because the building was being renovated,” Vold said. “But now I expect we’ll have an upswing.”

The new observatory will serve students enrolled in introductory astronomy, a popular way for William & Mary’s humanities and social-science majors to fill science GER requirements. Images from the 14-inch, computer-controlled Meade telescope can be piped down into the building’s lecture halls. Logistics would preclude intro lab sections from using the big scope directly: Vold says he’s comfortable with five to maybe eight people in the observatory dome at one time, “unless they start to mill around too much.”

At the transit party, Vold called eight-person shifts—warned of the dangers of excess milling—into the dome. Others took turns at eight-inch telescopes set up by volunteers from the Student Physics Society. There was more waiting than watching, as broken cloud cover drifted across the sun, which broke through the clouds with enough regularity to give the partiers a view of Venus, a teeny black circle as seen through the solar filters, crawl across the surface of the sun.

Cloudy skies and light pollution are the twin curses of telescope astronomy, and Vold has developed a philosophy for unpredictable conditions.

“It’s like having a 15-year-old,” he says. “You just have to be flexible. You schedule something for eight o’clock at night. If it’s cloudy, you schedule it for the next eight o’clock at night.”

So that he doesn’t have to be on hand for each and every clear night, Vold is training a few students to operate the observatory. The observatory’s computer can point the telescope and rotate the dome to reveal any of a constellation of heavenly objects. It’s not a steep learning curve, but, Vold says, one does not simply walk into the observatory and type “crab nebula.”

“The typical young student’s approach to learning computers, which usually works really well, is to just try everything out until you figure out how it works,” Vold explained. “If you do that with a computer-guided telescope mount you can ruin a lot of things.”

The dome itself requires careful tending, too. The first rule, Vold says, is to keep the door shut. “If the dome starts to rotate while the door is open, it will come off its track. It can be fixed, but it takes five or six people to lift it back onto the track and we just don’t want to go through that hassle.”

Vold teaches an annual freshman seminar in astrophotography and says he’s found that even experienced astronomers relate better to photos of the heavens than to direct observation through a telescope.

“You look through the eyepiece of all but very large telescopes and whatever there is to be seen is in black and white, because the light is not strong enough to turn on the color sensors in your eye,” he said. “The camera works a little differently. The camera just collects photons of all colors—it doesn’t matter what color, it just collects them as long as the shutter is open.”

Therefore, he explained, the camera is thousands of times more sensitive than your eye. It’s the reason why you won’t be able to look through any telescope and see with your eye an image to match those stunning shots of far-off places in the heavens.

Vold’s interest in astronomy began at the age of six. He comes by it honestly, as his mother’s grandfather was Robert Grant Aitken, director of the Lick Observatory in California. Vold inherited some of his grandfather’s notebooks and negotiated a deal with the current Lick administration. They got the notebooks and Vold got to take a break from his job doing astrophotography at the Thomas Harriot Observatory to spend some time doing astrophotography on the Great Lick Refractor—his great-grandfather’s telescope, 57 feet long, built in 1879 and still in use.

Vold says only half the freshmen in his astrophotography seminar are headed for science majors, a mix of intellects that makes for “an interesting clash of ideas,” as he puts it.

“The science students are entranced by things like how do you measure the distance to stars—all the quantitative things you would think somebody in science might want to do,” he said. “The non-science students look at the pictures and just go wow. Then they try to apply basic ideas of form and artistic merit to the photos.”

But all of them have one interest in common: the fate of Pluto.

Some come down on the side of scientific accuracy, Vold says, and support the 2006 demotion of Pluto to “dwarf planet” status. Others adopt a “once a planet, always a planet” stance.

And Vold himself?

“I think there ought to be a grandfather clause. It’s just sort of common sense,” he said. “Besides, when you tell people that Pluto is a planet—but it’s an exception—they’ll ask what you mean and you can make it a teachable moment.”

This story appeared in the winter, 2012 issue of the William & Mary Alumni Magazine.