In ‘Ballads of Broncos,’ Jacob Brown ’26 examines, reimagines gender and sexuality in Western verse

In the popular imagination, the words “American West” typically conjure up archetypes of manhood plucked out of the nineteenth century: cowboys, sheriffs, gunslingers, outlaws. Reinforced by literature, cinema and ubiquitous imagery for generations, these masculine figures remain unavoidable to this day.

In the popular imagination, the words “American West” typically conjure up archetypes of manhood plucked out of the nineteenth century: cowboys, sheriffs, gunslingers, outlaws. Reinforced by literature, cinema and ubiquitous imagery for generations, these masculine figures remain unavoidable to this day.

But William & Mary English major Jacob Brown ’26 has found that there is much more to Western manhood than these hackneyed images suggest — and there always has been.

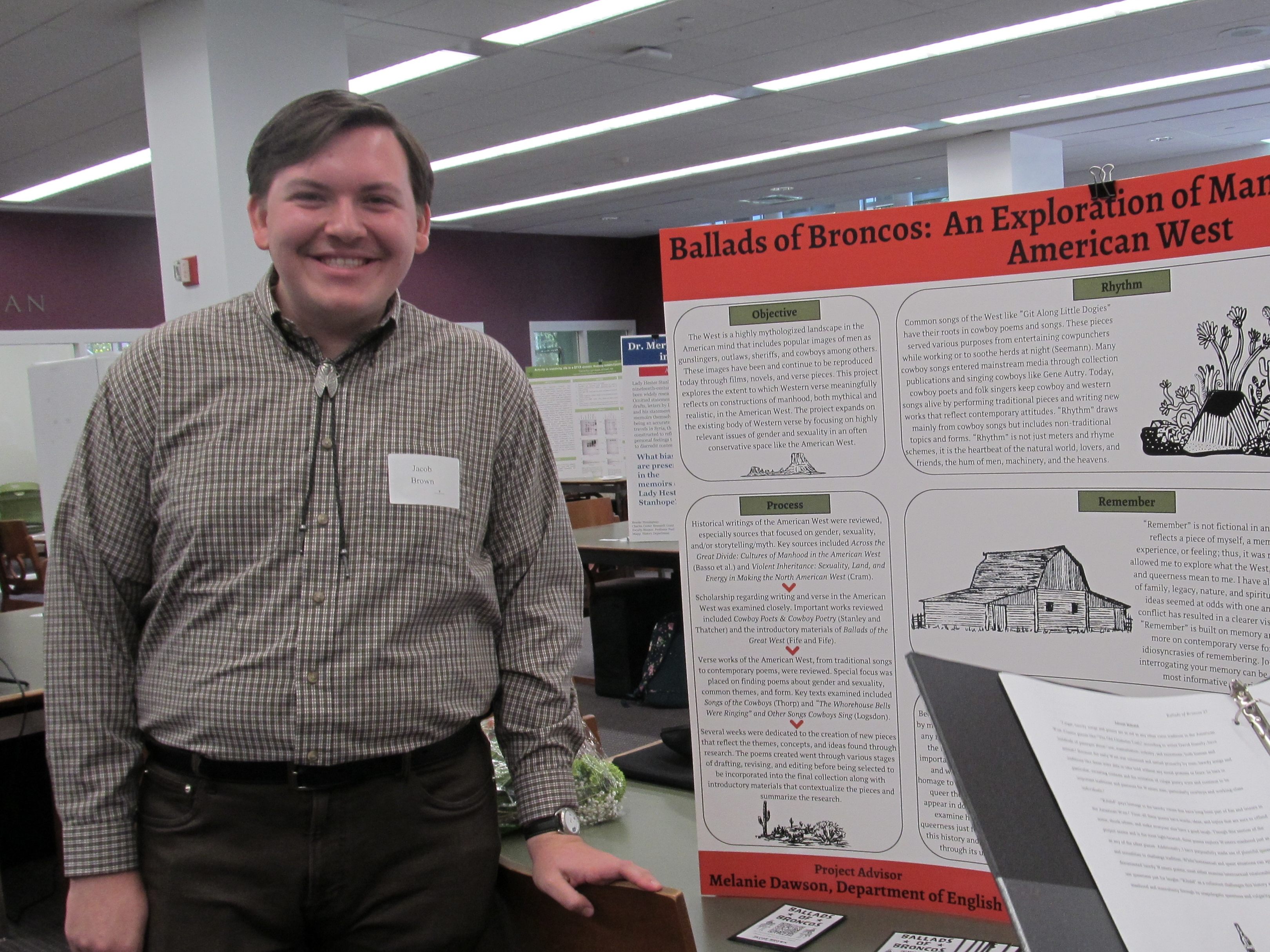

Brown’s summer research project, “Ballads of Broncos: An Exploration of Manhood and Verse in the American West,” supported by the Charles Center and featured at its Fall Undergraduate Research Symposium on Sept. 20, deconstructs gender and sexuality within Western mythology through the examination and original composition of poetry and song.

Through these media, Brown explained, “the voice of queer people in the American West is becoming louder.” At the same time, though, a male-led “cowboy church movement” and a wider “Christian conservative movement that’s very strong in the West” often harken back to an imagined Old West as the model of a narrowly defined traditional, heteronormative manhood.

Brown’s project highlights this clash and brings diverse perspectives to the fore. According to his advisor, Melanie Dawson, Sara E. Nance Professor of English, “Jacob was interested in exploring wide-ranging representations of American manhood in verse, particularly those that undercut ideals of mainstream Western masculinity.”

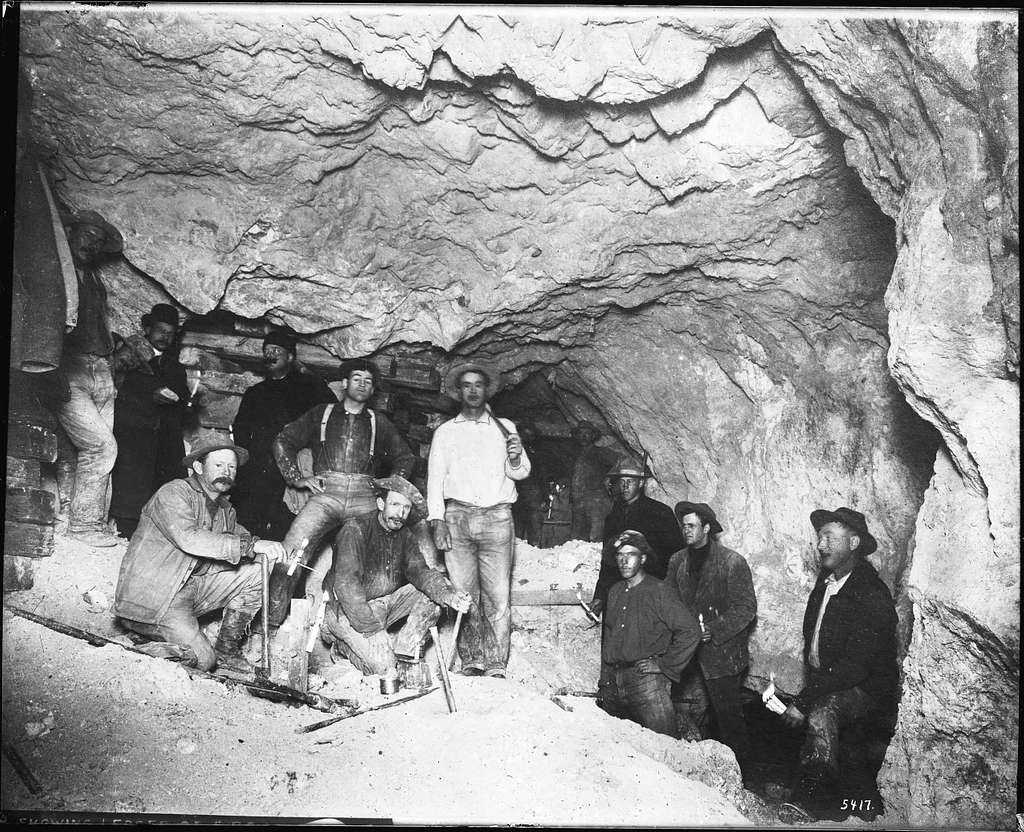

“There is a deep queer history in the American West,” Brown said, “especially considering how a lot of the early settlement of the West,” notably in mining communities, consisted “primarily [of] men. So, obviously there were very rich male-male relationships that developed.”

As Brown observed, published histories of the West, starting with Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis” in 1893 and extending through most of the twentieth century, have long failed to acknowledge the possibility and the reality of homosocial and homosexual relationships in the region. Within the past year or two, however, Brown has noted a blossoming of Western scholarship by queer historians disrupting this trend. And, in the realm of literature, recent collections of cowboy poems by queer authors — many quite “bawdy” — have illuminated experiences often omitted from nineteenth-century documents.

Still, queer themes are not exclusive to contemporary poetry, according to Brown. His study of the earliest collections of Western ballads and songs he could locate, dating to the 1910s but including verse from well back into the 1800s, revealed works that he described as “very sexual in nature.” Though these early poems often referred to homosexual encounters humorously, Brown pointed out, they were still working through the reality of queerness.

Indeed, Brown found a long tradition of literature that examines “those more intimate, softer moments between men.” Poetry that focuses on man’s relationship to nature in particular, he said, “softens the idea we have of masculinity,” countering “rough-and-tumble images of men as cowboys and ranchers and loggers” who dominate the wilderness.

Brown placed the remarkable variety of poems he discovered “in debate with one another to find places where there is challenge, places where there is tension.”

What truly distinguishes Brown’s project, though, is that he did not merely spectate this artistic conversation. As a young man born and raised in the West, he chose to participate in it himself by authoring poems of his own.

“It was because of the fact that I’m from Texas that I did this project in the first place,” he said. The work had a personal dimension at “every level,” as he channeled his exposure to Western media and iconography in his early life into creative production.

Brown is confident that writing poems to pair with those he had read allowed him to carry out a more insightful analysis.

“Poetry is a very personal genre,” he said. “Creating it, rather than just consuming it, … helps you connect with the material” and “connect with the artform.” Conventional meters and rhyme schemes became tools for Brown to subvert gender norms in his own work as had the queer poets he studied.

In addition to enriching academic and artistic discussions of masculinity, Brown believes his project underscores the need for more scholarship that centers authors other than straight, white colonizers from outside the American West. As an English major, he is frustrated by the fact that, “when we talk about late nineteenth-century/early twentieth-century literature, we have a tendency to really only think about what was happening in the eastern United States,” especially the Northeast. Writers from this part of the country do not represent the totality of American literature at the time, but, according to Brown, scholars have often overlooked other regional literatures or treated them as trivial. He sees his his work as one step toward remedying this oversight.

Now a junior, Brown looks forward to applying what he has learned from this project to an honors thesis, in which he plans to turn back toward the Northeast to examine Little Women author Louisa May Alcott. His work on Western poetry, he said, has given him the perspective to contextualize Alcott within a particular region at a particular time.

For Brown, though, “Ballads of Broncos” is, above all else, a testament to the skills students can gain through the research experiences that the Charles Center makes possible. Learning how to delve deeply into a topic and locate and analyze sources has not only equipped him for the remainder of his work as an undergraduate. It has also helped inspire him to pursue a Ph.D. in English.

“I’d love to be a professor,” Brown said. “I’d love to be able to do research for the rest of my life!”