The Muscogee Language Documentation Project

Language is essential to community. Jack Martin, Professor of English and Linguistics at William & Mary, works with Native American communities across the American south to document and revitalize Native languages. With funding from the Faculty Grants Fund, Martin has embarked upon the latest phase of that research: creating a digital dictionary of the Muscogee language. Martin’s interest in languages began as an undergraduate at UCLA where he took a course that specialized in a Uto-Aztecan language called Mono. He realized then the potential impact that studying endangered languages could have. “When you work on lesser-studied languages, you very quickly learn new things about what’s possible in language in general,” Martin said, “and you’re also contributing to the community.”

Martin’s interest in languages began as an undergraduate at UCLA where he took a course that specialized in a Uto-Aztecan language called Mono. He realized then the potential impact that studying endangered languages could have. “When you work on lesser-studied languages, you very quickly learn new things about what’s possible in language in general,” Martin said, “and you’re also contributing to the community.”

The work of documenting Native American languages is particularly urgent since the number of speakers has been declining. The Muscogee (Creek) Nation, located in Oklahoma, is one Native nation which has experienced that decline.

In the 1980s, Martin estimates, there were about 5,000 speakers of the Muscogee language; today, there are fewer than 400. When Martin began studying Muscogee in the 1980s and 1990s, Native American communities were less interested in language documentation. “They had thousands and thousands of speakers then, church services were in Muscogee, and there were radio broadcasts in the language. It’s the recent decline in the number of speakers that’s really affected how the tribes are viewing these language projects now,” he said.

The centrality of language to community means that the project of documenting Native languages is not only important for academics interested in linguistics but also for Native communities to retain a critical part of their culture and history.

The centrality of language to community means that the project of documenting Native languages is not only important for academics interested in linguistics but also for Native communities to retain a critical part of their culture and history.

Much has changed in the field of language documentation since Martin joined William & Mary as a professor in 1993. At that time, Martin said, linguists operated as “lone wolves” and drove their own research agendas into Native American languages. Linguists now employ community-based models of research, collaborating with the Native communities whose language they study and supporting the communities’ language goals.

Martin’s research exemplifies the collaborative nature of modern language documentation: he works alongside citizens of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in a mutual project of language documentation.

In 2000, Martin co-authored a major contribution to the study of the Muscogee language with Margaret McKane Mauldin (Muscogee), who was awarded a Doctor of Humane Letters from W&M in 2005. Their book, A Dictionary of Creek/Muscogee, was published in 2000 by the University of Nebraska Press.

Josh Piker, a professor of history at William & Mary and scholar of the Muscogee-speaking Creek Nation, used the dictionary (which he calls “THE definitive dictionary of the Muscogee language”) frequently for his own research. He also noted that “it’s a wonderful resource for the Creek Nation and its citizens that they can deploy as part of their language revitalization projects.”

Josh Piker, a professor of history at William & Mary and scholar of the Muscogee-speaking Creek Nation, used the dictionary (which he calls “THE definitive dictionary of the Muscogee language”) frequently for his own research. He also noted that “it’s a wonderful resource for the Creek Nation and its citizens that they can deploy as part of their language revitalization projects.”

In recognition of the dictionary’s significance, the University of Nebraska Press will soon publish a second edition.

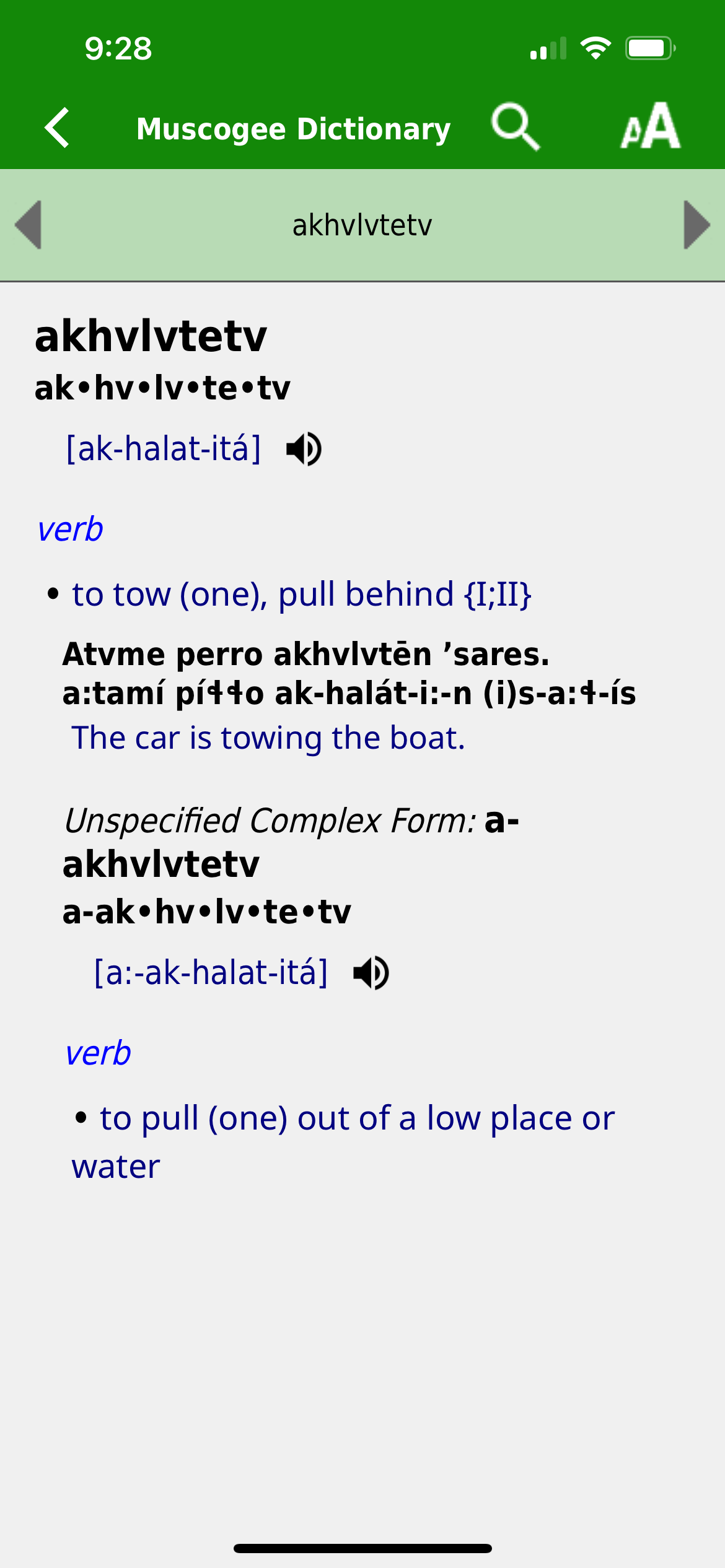

There will be several key distinctions between the first and second editions. Most importantly, for Martin, the copyright for the second edition will be held by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation rather than a university press. And the new edition will include not only a printed book but also a website and an app.

The digital versions will provide an easier way for learners to engage with the dictionary, since they can access it through their phones, tablets, and laptops. Those versions also have an audio component, which “makes the language come alive,” Martin said.

In February 2024, with the support of the Faculty Grants Fund, Martin traveled to Thlopthlocco, a federally recognized Muscogee (Creek) tribal town located within the state of Oklahoma. There, he collaborated closely with Linda Bear Wood, a Muscogee speaker, who advised Martin on the accuracy of the dictionary entries and provided recordings of her pronunciation of the words.

Dakota Kinsel ’26 helped turn Wood’s recordings into audio files for the digital dictionary using Audacity software. As a Navajo, she recognizes the importance of language for the sustenance of a culture and regularly speaks the Navajo language with her grandparents.

Dakota Kinsel ’26 helped turn Wood’s recordings into audio files for the digital dictionary using Audacity software. As a Navajo, she recognizes the importance of language for the sustenance of a culture and regularly speaks the Navajo language with her grandparents.

Kinsel acquired valuable research skills while working with Martin. Yet even more important, she said, was the sense of personal purpose that came with the project.

“Working on this project with such a meaningful purpose had a profound impact on me as it brought me closer to connecting with other Native American tribes and developing a greater sense of empathy, culture, and the importance of linguistic diversity,” Kinsel said.

Martin’s research documents and expands access to Native American languages, a project of vital importance to Native American communities as well as academic scholarship.

Skip to main content

Skip to main content