The college that's a university

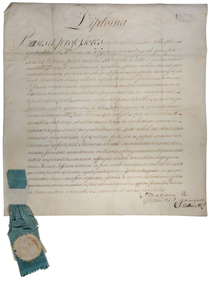

Thomas Jefferson's honorary degree diploma to be on display at the Muscarelle Museum

The following story originally appeared in the winter 2017 issue of the W&M Alumni Magazine - Ed.

“The President and professors of the University or College of William & Mary to all to whom these present letters shall come, greetings.”

That’s the warm welcome proffered, in Latin, at the beginning of the 1783 honorary degree bestowed upon Thomas Jefferson, naming him doctor in civil law.

Stretching across the centuries to the entire William & Mary community, the greeting will prove even warmer when the diploma is exhibited here in 2017.

The honorary degree diploma, on loan from the Massachusetts Historical Society, will be on view at William & Mary’s Muscarelle Museum of Art at the beginning of February, providing a highlight for the 2017 Charter Day celebration on Feb. 10. The diploma will remain on display until Commencement.

“It will be wonderful to exhibit Thomas Jefferson’s diploma, an institutional treasure, in time for William & Mary’s ‘birthday.’ We are exceedingly grateful to the Massachusetts Historical Society for lending it to us,” says Jeremy Martin Ph.D. ’12, assistant to the president and provost.

It is Martin who led efforts on the diploma’s exhibition and is the latest person to research the document’s most curious aspect, apparent immediately to those who know Latin, or at least Google Translate: the use of “university.”

It is Martin who led efforts on the diploma’s exhibition and is the latest person to research the document’s most curious aspect, apparent immediately to those who know Latin, or at least Google Translate: the use of “university.”

It’s fascinating that in 1783, less than 100 years after the royal charter was issued and not long after the grammar school for boys and the Brafferton Indian School ceased operating on campus, W&M was already calling itself a university. The grammar school in particular usually had a larger student body than the college proper.

“This official document — the only diploma Jefferson received from his alma mater — demonstrates the acceptance of calling William & Mary either the University or the College,” Martin explains. “It wasn’t the first time, nor was it a one-off. There were consistent and deliberate references to William & Mary as a university in the 1700s, not unlike efforts to communicate W&M’s status today.”

Universitatis seu collegii?

Of course, the 1693 royal charter states flatly that the institution “shall be called and denominated, forever, the College of William & Mary, in Virginia.”

But Susan Kern Ph.D. ’05, executive director of the Historic Campus and noted Jefferson scholar and historian, has found early references to W&M as a university. Eighteenth-century letters suggest that as far as William & Mary President James Madison, Law Professor George Wythe, George Washington and Jefferson were concerned, William & Mary’s status as a university was settled on Dec. 4, 1779, with the adoption of reforms creating professorships of anatomy and medicine, modern languages, and law and police.

At the time, Jefferson was governor of Virginia and a member of W&M’s Board of Visitors. He pressed the changes that also disbanded the divinity school and the grammar school. The Brafferton Indian School had been closed since the 1777 advent of rebellion, when its funding from the Brafferton estate in Yorkshire, England, ceased to flow.

“Jefferson wanted to do away with the grammar school because it was a distraction to the scholars, as he called the college-level students,” Kern says. “He wanted to change the Brafferton to send missionaries among the Indian tribes, instead of bringing boys to Williamsburg. He revised the philosophy school program — what we would say is the undergraduate curriculum — and he hoped to do away with the divinity school; his ideal model was secular education.”

It’s clear that Jefferson knew exactly what he was doing when he pushed to add America’s first law school at William & Mary. Earlier that year he had introduced state legislation, the famous Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge that, in addition to other measures, proposed to amend W&M’s constitution to include more science in the curriculum and “to make it in fact an University,” he recounted in his autobiography.

That bill stalled for more than a decade, until a weakened version passed in 1796 as an Act to Establish Public Schools. But Jefferson had already largely met his goals at W&M through the 1779 reforms, though he failed to excise the church entirely, Kern says.

Jefferson’s unhappiness on that last score grew as William & Mary remained essentially a church school, leading to his decision to establish the wholly secular University of Virginia. Unlike W&M, which remained private until 1906, U.Va. was a state school from its outset.

Almost immediately after the 1779 reforms, those in and around William & Mary began regularly calling it a university. (Interestingly, Carlo “Charles” Bellini, a year before the reforms, identified himself in a letter as “Professor of modern languages in this University of Williamsburg.”)

Five days after the Board of Visitors adopted the reforms, on Dec. 9, 1779, student John Brown, worried about increased expenses, wrote to inform his uncle that “William & Mary has undergone a very considerable Revolution; the Visitors met on the 4th Instant and form’d it into a University, annul’d the old Statutes, abolish’d the Grammar School…”

Then the following year, writing to the president of Yale about William & Mary’s finances and operations, W&M President James Madison stated, “The Doors of the University are open to all, nor is even a knowledge in the Ant. Languages a previous Requisite for Entrance … The public Exercises are 1st, weekly. The whole University assemble in a convenient apartment…”

In the same letter, however, Madison said, “The first Plan of our College was imperfect,” reflecting a tendency to use the terms “college” and “university” interchangeably, Kern notes. This continued over the next few years.

In 1781, W&M’s Madison updated his cousin in the Continental Congress, James Madison, who would later become president of the United States: “The University is a Desert. We were in a very flourishing way before the first invasion … we are now entirely dispersed. The student is converted into the Warrior…”

Wythe wrote something similar to George Washington around the same time, telling him, “Last year, until the british (sic) invasion, the university was in a prosperous state.” But then a few sentences later, Wythe switched it up, referring to the “college.”

Washington also held to the pattern in his correspondence. On Oct. 17, 1781, he wrote to John Blair, “You may be assured Sir that nothing but absolute Necessity could induce me to desire to occupy the College with its adjoin (sic) Buildings for Military Purposes.” But 10 days later, Washington sent a note that he accepted “kindly the address of the President and Professors of the University of William and Mary.”

What’s in a Name?

Interestingly, before 1776, some colonial colleges weren’t even trying to be acknowledged as such, much less promoting themselves as universities. James Axtell, W&M history professor emeritus, who in 2016 published Wisdom’s Workshop: The Rise of the Modern University, writes that some of the institutions avoided even calling themselves “college.” Almost all of the nine colonial colleges lacked royal charters; their charters were signed by governors or colonial legislatures, causing some concern as they assumed the ability to award degrees. Yale, for example, “not daring to incorporate,” originally called itself a “collegiate school,” Axtell notes.

But by the late 1770s, William & Mary wasn’t alone in trying to establish itself as a university. Martin says the University of Pennsylvania has a particularly strong claim as the first American university.

Penn was founded as the Academy of Philadelphia in 1749, becoming the College of Philadelphia six years later. In 1765, it established a medical department (the first American medical school), awarding its first Doctor of Medicine degrees in 1771.

“After introducing medical education, the College of Philadelphia began speaking of itself as a university, though without officially changing its name,” says Martin.

In the late 1700s, the state legislature and school fought for control of the institution. In 1779, the state established the University of the State of Pennsylvania — the first American institution named “University” — from the college, but the school’s leadership rejected the action. For more than a decade, the College of Philadelphia and University of the State of Pennsylvania operated separately, until they were combined to form the University of Pennsylvania in 1791.

Harvard wasn’t called a university until the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution referred to it as the “University of Cambridge” and “The University” while still retaining use of “Harvard College.” Its medical school was established in 1782. (The Code of Virginia takes a similar approach in defining W&M’s legal name as “The College of William & Mary,” but uses “The University” in subsequent references.)

In the 1840s, Harvard’s governing corporation discussed the use of its various names, voting in 1849 that “the name ‘Harvard College’ is the legal and proper name of the university, to be used in legal and formal acts and documents…” It remains so for its undergraduate liberal arts program.

In the 19th-century antebellum period, American higher education as a whole wouldn’t reflect Harvard’s restraint. Academies, grammar schools and others began to declare themselves universities, to the consternation of many in academia. “By European lights, there were few, if any, bona fide universities in America,” writes Axtell.

A University named ‘College’

Of course, W&M is today unequivocally ranked as a research university by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. In 1964, William & Mary introduced Ph.D. programs in marine science and physics. Today, it offers doctoral degrees within humanities and social sciences, natural and computational sciences, the School of Education and the School of Marine Science. (See “It Takes a Research University,” Spring 2016.)

But like Johnny Cash’s “Boy Named Sue,” being a university named “College” can complicate things for faculty and staff who face outward from campus.

Henry Broaddus is W&M vice president for strategic initiatives and public affairs. Before that, he was dean of admission and associate provost for enrollment. So he’s been representing William & Mary to various parts of the world for more than a decade.

Broaddus says he suspects that W&M “sometimes gets short shrift” for the public good it does and the caliber of its research when not recognized as a bona fide university. W&M’s communications office periodically has to call members of the national and international media to request corrections of constructions such as “William & Mary College.”

From 2006 through 2014, Broaddus was part of a State Department-funded program that sent admission deans to American international schools outside of the U.S. to meet with their students — about one-third each from America, the host country and rest of the world — about stateside universities.

Foreign students in particular struggle to make sense

Of America’s higher education system. Broaddus recalls speaking with the daughter of a diplomat in the Ethiopian Embassy in India who was already “flummoxed” by the fact that Pennsylvania is a state but the University of Pennsylvania is private.

“Plus, there are plenty of liberal arts colleges calling themselves universities,” Broaddus says. “And among U.S. News & World Report’s top-50 national universities, there are seven that don’t use the word ‘university.’ Four of them are institutes. Three of them are colleges in name. Only one of those leads with the word ‘college’ in its formal title. You can guess which.”

Universitatis commune

As members of the W&M community will see for themselves this spring, Jefferson’s degree praises him for his ability in law, his humility and patriotism “illustrious not only in other matters but especially in championing American liberty.”

“All the fine arts seem to foregather in one man,” reads the diploma signed by W&M President Madison; Wythe as professor of law and police; Robert Andrews, professor of mathematics and philosophy and Bellini, professor of modern languages.

Historians believe Wythe authored the diploma out of admiration and affection for Jefferson, its wording a salve for the cuts Jefferson endured when his actions and inactions as a wartime governor were criticized. “For a deed well done he seeks his reward not from popular acclaim but from the deed itself,” Wythe wrote.

There is one final use of “university” at the end of Jefferson’s diploma, in reference to the William & Mary seal. Since the document opens with “university” and closes with “university,” perhaps the references were intended to signal to Jefferson that W&M’s leadership appreciated his efforts to elevate his alma mater above its royal name and colonial brethren.