Robin Looft-Wilson receives the 2009 Alumni Fellowship Award

|

|

A Gathering of Minds

The 2009 Alumni Fellowship Award Recipients Take an Interdisciplinary Approach

to Teaching and Research

BY BEN KENNEDY '05, PHOTOS BY MARK MITCHELL

William and Mary professors have long been renowned for their devotion to their students' classroom experience; today's scholars must also embrace a variety of disciplines and approaches to a swiftly changing academic world.

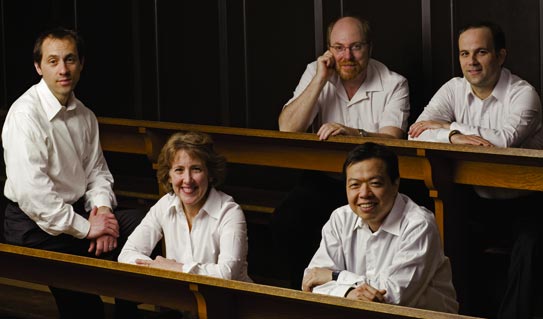

The recipients of the 2009 Alumni Fellowship Award -- Christopher Del Negro, Robert S. Leventhal, Robin Looft-Wilson, Paul F. Manna and Kam W. Tang -- are precisely those sorts of educators.

They will be recognized at the Fall Awards Banquet in September with a $1,000 honorarium, endowed by the Class of 1968 at their 25th Reunion. Beyond that, they will continue enriching students and expanding horizons, no matter which department they call home.

Robin Looft-Wilson

Associate Professor of Kinesiology

B.S., Physical Education and M.S., Exercise Science, University of California at Davis;

Ph.D., Physiology and Biophysics, University of Iowa

BY BEN KENNEDY '05

Mark Mitchell |

Robin Looft-Wilson studies the science of blood. Science is also in her blood: her father had a master's degree in meteorology and oceanography, so dinner table conversations often revolved around Einstein and black holes. As a kid, she wanted to be an astronaut, but she became hooked on science after her first semester in her master's program.

"From designing the experiment to analyzing results, I can't imagine anything more interesting," she says.

The

early years of her career were spent focused largely on space

physiology -- astronaut health. After conducting experiments for NASA

on how the circulatory system adapts to zero-gravity, Looft-Wilson got

a Ph.D. and started focusing on the basics of blood vessels.

Specifically, she studies how blood vessel mechanics influence

cardiovascular disease, one of the most dangerous and lethal conditions

in American health. In her work, Looft-Wilson looks at an amino acid

called homocysteine, high levels of which are a major risk factor for

atherosclerosis along with cholesterol.

"It's not as recognized and hasn't been studied as long as high cholesterol," she says, "but it's thought to be a very important contributing factor." Homocysteine levels can be increased by a diet low in B-vitamins and folate, which is common in Americans.

"We study how this affects blood vessel function: its ability to dilate and contract. [Homocysteine] impairs it," she says. "When the blood vessels don't dilate and contract appropriately, not only do you lose the ability to control blood flow to your tissues but it promotes atherosclerosis."

The real-world application of her research is not lost on her students, many of whom have relatives with cardiovascular problems.

"It seems like a lot of the students just want to know as much as they possibly can. In my physiology classes I present much more about pathologies and treatments," she says. "It's more of the medical aspects than I would have presented otherwise, but it all comes from student demand."

Looft-Wilson has her students read primary literature along with her lectures to ensure that she stays fresh and her students know about the cutting edge of research in her field. By learning to criticize and evaluate published findings, she prepares her students for even more rigorous graduate work. Her obvious enthusiasm is contagious.

"I've been amazed at how well students can read a paper and pick out the flaws. Some of these are real tough papers and are very technical. In essence, they are teaching themselves a whole new language, in addition to trying to understand the science," she says. "Some of them find flaws in the paper that I didn't find. I love when that happens; it's amazing."

Occasionally her students will request specific studies that have been in the news.

"When students are asking to do additional papers because they're interested in the topic, nothing's better than that. When the students are pushing me to work harder, I couldn't ask for more," says Looft-Wilson. "Those are the best moments as a professor here at William and Mary: when students exhibit that excitement. They want more, and they're asking more from me."

And the family enthusiasm for science may be genetic after all: her 9-year-old son Jacob is often hard at work playing with his toy molecule construction set.