A trip down the garden path leads a historian to...cryptozoology?

Holly Gruntner says she was “kind of trolling” in the archives of the American Antiquarian Society when she ran across something that she couldn’t resist.

Holly Gruntner says she was “kind of trolling” in the archives of the American Antiquarian Society when she ran across something that she couldn’t resist.

“It was that mystical period, at the end of a time in the archives,” she said. “You've seen everything that you knew you needed to look at. And you get time to sort of plow through less-obvious collections. You're not sure how fruitful they will be for your project — but they often yield the most interesting results.”

Gruntner is a Ph.D. candidate in William & Mary’s Harrison Ruffin Tyler Department of History. She recently completed a short-term fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society, delving into the society’s vast collection of original documents for material to complete her dissertation on kitchen gardens in early America.

“And so I was in the Jacob Porter papers, because I knew that he had taken some notes on botanical lectures,” she said. “I found some botanical materials that I was looking for.”

Gruntner and the reference-desk staff were trolling their way through the archive’s finding aid for the Jacob Porter papers when a certain title stopped them mid-troll. It was “An Attempt to Prove the Existence of the Unicorn.”

“Of course, we had to look at that,” she said. “You can’t not look at something with that title.”

Gruntner sat down with the original Porter manuscript, which turned out to be a handwritten translation of a French work by the 19th-century botanist Jean-François Laterrade. Porter’s translation of the “Unicorn Treatise” was published in the American Journal of Science and Arts in 1832. She found the treatise interesting enough to make it the subject of a post on the American Antiquarian Society’s blog.

Gruntner sat down with the original Porter manuscript, which turned out to be a handwritten translation of a French work by the 19th-century botanist Jean-François Laterrade. Porter’s translation of the “Unicorn Treatise” was published in the American Journal of Science and Arts in 1832. She found the treatise interesting enough to make it the subject of a post on the American Antiquarian Society’s blog.

A 19th-century discourse outlining evidence for the unicorn’s existence isn’t completely off topic for Gruntner’s study of the kitchen gardens of America’s non-elites from 1660 to 1830. She is particularly interested in what the gardens of common folk reveal about their knowledge and understanding of science.

“My biggest takeaway so far has just been how intensely intellectual every step of keeping a kitchen garden is,” she said. “This won't be a surprise to anyone who gardens. You really have to know a lot about weather and soil. There are challenging processes, like grafting a fruit tree. It was experimental: people were constantly observing their gardens and adjusting their techniques.”

She acknowledges that the gardeners of the time period she studies didn’t always make decisions by modern concepts of the scientific method. There was a lot of folklore involved — even astrology and superstition. But, she pointed out, there was a lot at stake.

“I try not to judge,” Gruntner said. “I try to take people on their own terms.”

She added that the kitchen gardeners commonly shared information, preserving and spreading horticultural best practices. For instance, if you knew your neighbor always had a good potato crop — and always was careful to plant his spuds during a waning moon in March, you would follow his example. The quality of your own harvest would be a data point to share with your neighbors and record in a garden journal to be consulted next spring (and perhaps read in a couple centuries by Holly Gruntner).

“So, I think I really don’t draw much of a line between folklore and science,” she said. “I’m interested in what’s real to them, what’s true to them. For these people, science and folklore — it’s all mixed together. And the line between the two can be really blurry, right?”

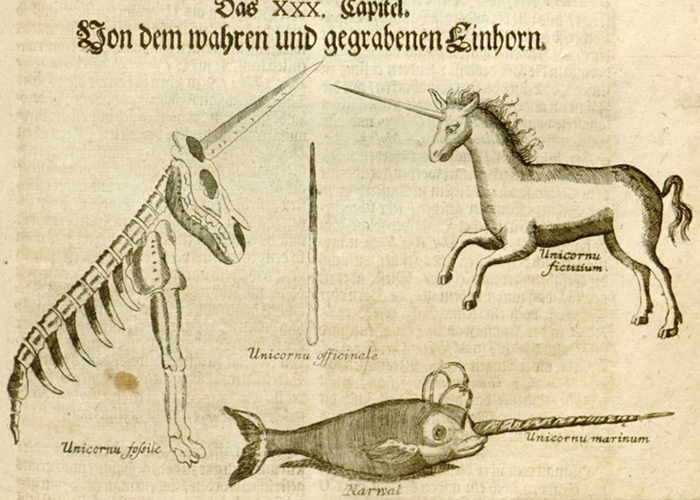

Gruntner says that blurry line is pretty thin when it comes to Laterrade’s evidence for the unicorn’s existence. She notes that Laterrade is quick to state that he’s not talking about the narwhal, the single-tusked sea mammal whose detached horn was often offered up as a relic of a regular, horse-like, unicorn.

He also has no time for tales about beliefs in various magical properties of the horn of the true unicorn. Such “falsehood or ignorance” obscures the real job at hand — demonstrating the existence of the creature, he wrote.

Laterrade cites numerous Old Testament references to unicorns, writing during an era in which the Bible was held in high esteem as a general reference. Unicorns are also mentioned by Pliny the Elder and other respected authors, he writes. Laterrade adds proof in the form of a unicorn skeleton, discovered in 1663 what is now Germany, and “sent to the Princess Abbesse.” Gruntner urges that Laterrade’s claims should be viewed in context of the times.

“We’re talking about the 1830s, here,” she said. “This was a time of really explosive, intense discovery. They were finding all kinds of things: mammoth and mastodon skeletons. It was a period when a lot of things were discovered that previously people might have considered to be impossible.”

And consider the platypus: A duck-billed, egg-laying mammal with poisonous spurs. It’s an animal infinitely more preposterous than a unicorn — and not blessed with a single reference in the Bible.

“Horses exist and a unicorn isn’t that different than a horse. So, I can imagine people being predisposed to think that something like a unicorn could exist, too,” she said. “Because, why not? All those other things existed.”

She stresses that her scholarly purview is not whether crops planted in certain astrological signs really will stand drought better, or even if unicorns exist.

“I’ll leave it to the hard scientists to tell me what’s true or not,” Gruntner added. “But I’m interested in why something was true to the people I’m studying. Why was is real to them?”