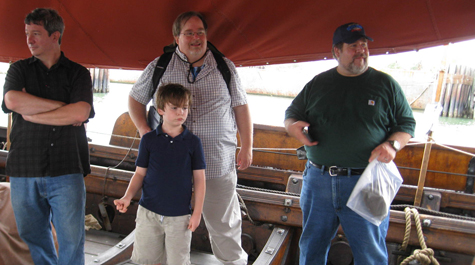

W&M professors, students climb aboard history

Two William & Mary professors recently took students 45 miles from campus and 900 to 1,200 years back in time.

Visiting Professor of English Kevin Kritsch and Professor Suzanne Hagedorn of Medieval and Renaissance studies accompanied students from four of their classes to Norfolk in late September, where docked was the Draken Harald Hårfagre, the world’s largest Viking sailing ship built in modern times. Crafted from materials used throughout history and based on archeological knowledge of Viking war ships between 750 and 1100 AD, the ship recently concluded a 14-harbor tour from Maine to South Carolina.

“It’s easy, when you’re dealing with literature, that it remains an abstraction,” Kritsch said. “I think having that sort of tangible experience with which to attach the literature is helpful. It’s important to take learning outside of the classroom.”

The trip received funding from several sources: the dean of Arts & Sciences and the Charles Center through the Community Scholars fund, as well as the program in Medieval & Renaissance studies and the English department.

“One of the things I Iike about William & Mary is the willingness on the part of the students and professors to engage and go out in the community when things like this come along and you have a chance to see living history,” Kritsch said.

Kritsch’s English 203 course incorporates the study of Old English texts in which either Vikings appear or are linked to Viking culture. His students read poems, he said, examples of monumental verse that celebrate success or lament failures in fights against the Vikings.

Hagedorn had just finished teaching the “Odyssey” in her Epic and Romance course, and her Medieval Literature class was studying “Beowulf,” a poem that starts out with a funeral in which a dead Danish king is sent out to sea by his people in a ship loaded with treasures.

“While the Viking ship is laid out slightly differently than Greek ships, the construction and experience of being on a ship powered by sail or by rowers certainly resembles what Homer describes in his epic,” she said. “I hope that they enjoyed seeing the sights, sounds and smells of a real Viking ship and got to understand and appreciate its scale. For me, one of the biggest surprises was the smell of the ship, which was wonderful — wood and linseed oil. That's the kind of sensory experience that you can't have by looking at a picture or watching a video.”

One member of the party, Emma Eubank ’22, wasn’t taking a class with either professor. But she said she’s always loved everything Nordic. Norse mythology used to be her favorite bedtime reading growing up.

The History Channel’s Vikings show is one of her all-time favorites.

She wrote a paper on Thor’s evolution while in high school and asked Kritsch to review it. That’s when she learned about the Draken’s scheduled appearance in Norfolk.

“The Draken Harald Hårfagre is definitely proof of human determination,” she said. “It was built and sailed authentically from Norway to Canada to the United States, and it toured the U.S. Great Lakes as well. The crew couldn’t bathe while at sea, had little privacy or room at all and had to rely only on themselves and each other to physically push themselves across the Atlantic.”

Student Bailey Ward ’22 grew up in a family that enjoyed European history — especially that of Great Britain.

“In order to contemplate British history,” she said, “one must study Norse influence with Anglo-Saxon England and the English language.”

Ward said she was impressed with the structure and fastidious craftsmanship of the Viking longboat.

“Not only did the craftsmen construct it with practicality in mind but also religion and other cultural influences,” she said. “The ships were built to be flexible in order to ride the waves rather than crash into them. They would also carve religious, pagan motifs and sayings into certain parts of the ship.”

The education started long before the group reached Norfolk. On the bus ride over, Kritsch said, they discussed the origin of the word “Viking.” Kritsch explained that the word is thought to come from an old Norse vikingr, a word used to refer to “pirate” or “freebooter.” word that means “to go a raiding.” Though not universally accepted, many scholars believe the root stems from the Norse word for ‘a bay' or 'inlet.'”

“So, they would all sail out on raiding voyages, pillaging from bay to bay,” he said. “We talked about the popularity of some of the TV show Vikings, which has been a great boon to Medieval studies by piquing interest with students.”

The group was taken throughout the ship by several of the 34 crew members, male and female, who explained that the ship differed from other Viking vessels because it was powered by 25 pairs of oars, two men to an oar. They gave the visitors a taste of some of the dangers involved in the voyage, including a mast that snapped, fell and trapped one of their colleagues below deck for several hours.

“I can’t imagine ever doing something so dangerous but simultaneously liberating,” Eubank said.

The students weren’t the only ones to derive benefit from the experience. It touched Hagedorn on several fronts.

“I'm not a sailor and don't know much about sailing, so hearing stories from the crew and seeing the ship helps me better understand the epics where people sail and spend time aboard ship.

“Moreover, it gave me a chance to see my students in a new environment and to see what engages them outside of our usual subject matter.”

Ward summarized the uniqueness of the adventure.

“Usually museum exhibits are supposed to be seen, not touched,” she said. “However, visitors could climb aboard the Draken and hear from those who have sailed it across the Atlantic. It’s always a pleasure to interact with living history."