Ghost forests present coastal Virginia with new haunting reality

The month of October inspires many frightening tales of creatures in the dark – of vampires, werewolves, and shapeshifters – that entertain more than terrify, perhaps because they are merely fictional tales of horror and woe.

The month of October inspires many frightening tales of creatures in the dark – of vampires, werewolves, and shapeshifters – that entertain more than terrify, perhaps because they are merely fictional tales of horror and woe.

Many of the more haunting realities we are faced with, however, are neither myth nor fantasy, but are rooted in evidence-based research into increasingly dramatic local impacts of global climate change.

Sophia Heilen ’26 is uncovering evidence of a new kind of unnatural shapeshifting quietly occurring around us: many of the state’s coastal forests are being killed in a transition to saltwater marshes due to recent sea level rise.

A double major in data science and environment & sustainability, Heilen is working with Assistant Professor of Geology Dominick “Dom” Ciruzzi to combine her interests and locate “ghost forests,” or the remains of a woodland area, on Virginia’s coast.

According to the National Ocean Service, this transition starts with the poisoning of live trees by saltwater, “leaving a haunted ghost forest of dead and dying timber.” Many of these decaying trees still stand where abundant forests once existed.

According to the National Ocean Service, this transition starts with the poisoning of live trees by saltwater, “leaving a haunted ghost forest of dead and dying timber.” Many of these decaying trees still stand where abundant forests once existed.

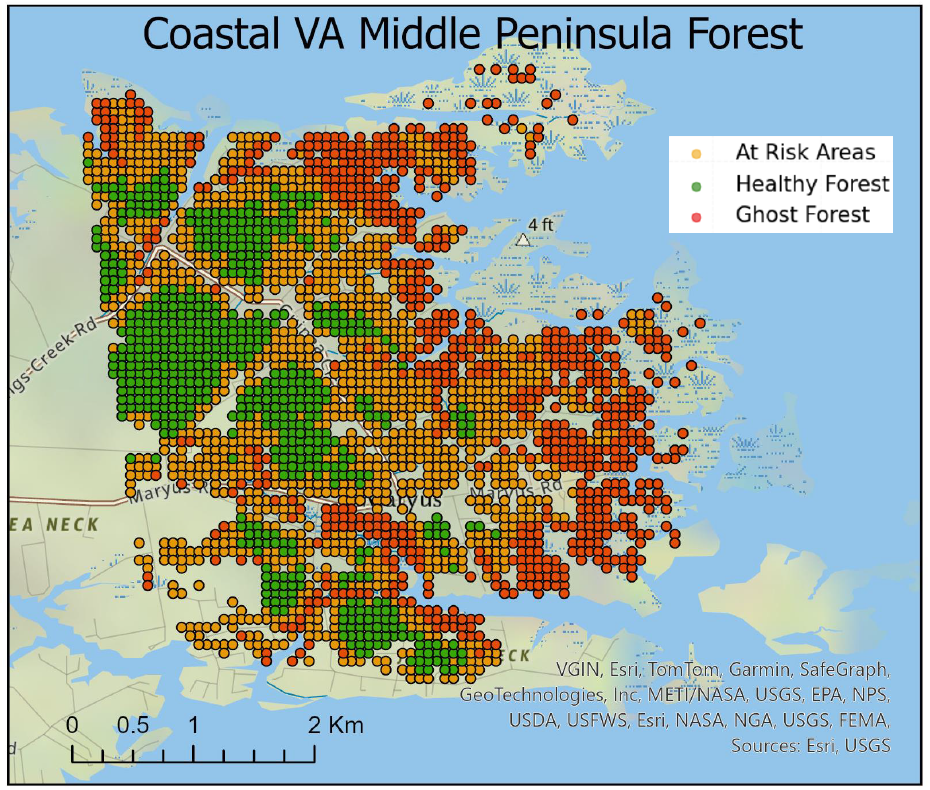

Heilen is specifically looking for environmental indicators like land use, elevation, and sea level rise to create a ghost forest vulnerability map to be used in future conservation measures.

“There’s a lot of research being done on how to identify those areas so that you can create conservation strategies,” Heilen mentioned. “But because this phenomenon is so new, there’s not a lot of variables being used. The intent of my project is to broaden the realm of what variables you could use and see how they can be used in combination to identify ghost forest areas.”

Heilen primarily researched remotely this past summer with financial assistance from the Charles Center Climate Change Scholarship Fund. She has been mapping threatened areas by using data from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration satellite technology named the Ecosystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station and evaluation tools such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index.

“You’re measuring how much water is evaporating out from a whole area, then you might see an area with a lot of evaporation and think that those trees are photosynthesizing and healthy,” Heilen explained. “If you see that they’re not photosynthesizing, they’re not evapo-transpiring, and therefore they’re either dying or on their way out in the future.”

Her eureka moment came when she realized that combining these indicators was a far more powerful strategy than focusing on one indicator to map forests. By measuring moisture, vegetation, temperature, and other environmental factors found in satellite imagery, she found a “very clear clustering between healthy forests and ghost forests.”

Her eureka moment came when she realized that combining these indicators was a far more powerful strategy than focusing on one indicator to map forests. By measuring moisture, vegetation, temperature, and other environmental factors found in satellite imagery, she found a “very clear clustering between healthy forests and ghost forests.”

Heilen will present her work over winter break at the American Geophysical Union Conference in Washington D.C., where she will connect with other researchers investigating similar topics. She said that she hopes to continue this research during the spring semester and further explore the intersection of environmental science and data science after graduation.

Heilen will present her work over winter break at the American Geophysical Union Conference in Washington D.C., where she will connect with other researchers investigating similar topics. She said that she hopes to continue this research during the spring semester and further explore the intersection of environmental science and data science after graduation.

The most rewarding part of her work, Heilen said, was meeting community members who have seen their own land and surrounding forests impacted by sea level rise. Hearing their stories helps draw a direct connection between the lives affected by climate change and her long hours behind the computer.

“It’s been really cool to talk to people who are actually seeing the effects, whereas I’m not really seeing it on the ground,” she explained. “To then connect it to someone’s real-world experiences and see that there is value in this research was a really fun experience and definitely motivated me to continue this research in the future.”

Heilen’s biggest piece of advice for student researchers, though, is to find a mentor and begin by exploring a topic of deep personal interest.

“I started with a bubble map with all of these different topics that I was interested in and just started with the key ones that I liked,” Heilen said. “The more you start delving into it, the more you realize that there’s all of these other branches that come off of that.”

While conservation research like Heilen’s can’t protect us from the haunting stories of immortal werewolves and vampires, it can lead us toward solutions for real, scarier phenomena, including the forest specters resulting from climate change.