Hart's book explores the little-known Robert Frost

There’s a 68th on the way.

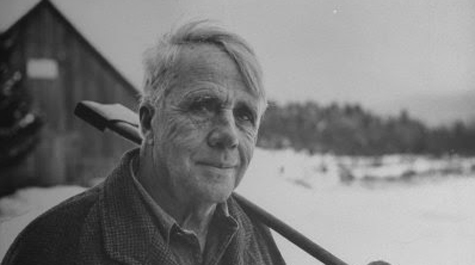

William & Mary English Professor Henry Hart expects his biography — titled The Life of Robert Frost — to be available in early April.

The question is: If one of the most famous poets in history has had 67 books written about him, can a 68th really break new ground?

{{youtube:medium:center|83l5FOJF1sc, W&M Professor Henry Hart discusses his new book}}

Yes, Hart answered confidently, and publisher Wiley-Blackwell agreed. Hart’s book, he said, distinguishes itself from other biographies by focusing on the psychological aspects of Frost’s life and on the importance of his family to his poetry.

“I wrote about facets of Frost that weren’t all that well known or touched on,” he said. “You look at the poetry; there’s a lot of darkness that comes out of Frost’s depressions.

“I did a lot of research, read almost all of the published letters, and sometimes he’s quite candid about his own psychological problems –- and definitely the problems in his family.”

When Hart, the Mildred and J.B. Hickman Professor of English and Humanities at W&M, was approached to do the work by a former professor of his at Dartmouth who’d written one Frost biography and didn’t want to do another, the assignment was merely to “plow through the existing biographies and compile an updated, scholarly biography.” No original research was required.

“And that’s how I [initially] approached it,” he said.

But that changed.

Hart, who taught Frost for years, felt a kinship with the poet in part because they had a New England background in common. He was drawn to Frost because he shared Frost’s passion for nature and farming activities, but also because he was always interested in how Frost wrote about those activities in such engaging ways.

“So many of the poems of Robert Frost were about activities I knew well growing up [in New England],” he said. “Frost wrote about … [harvesting] Christmas trees, a lot of poems about sawing and chopping wood. I used to sell firewood, and on [our] Christmas tree farm we often had to cut down big trees because they shaded the Christmas trees and they wouldn’t grow. Frost had some poems about mowing; I spent a lot of time mowing [around the trees].”

Hart buttressed his research by developing relationships with two of Frost’s descendants, granddaughter Lesley Lee Francis, who wrote two books on Frost, and grandson John Cone, a Roanoke architect whose firm helped renovate Blow Hall.

He also became very interested in the genealogy of the Frosts. When he did research on their family tree, he found information that shed new light on parts of Frost’s life that will surprise his fans.

Who was Nicholas Frost, and how many were there?

That included investigating the mystery of the “two” Nicholas Frosts who supposedly hit American shores in the early 1630s.

One Nicholas was arrested and charged with stealing from Native Americans, as well as “fornicating” with them – “that’s the word they used to describe his behavior,” Hart said.

The crimes were considered so serious that he was banned by a magistrate and told that if he ever returned to America he would be executed. Some Frost historians say he fled, but stayed in hiding in New England. Others say he returned to England, retrieved his family, and then came back to America. Two Frost relatives maintain in an extensive genealogical book that one Nicholas Frost was a criminal who was banished from New England and a second Nicholas Frost was the dignified, prosperous patriarch of the Frost family.

“Nobody is quite sure what happened.”

What is known is that someone named Nicholas Frost had a wife and daughter kidnapped and then killed by Native Americans in 1650. One of Nicholas’s sons dedicated the rest of his life to fighting Native Americans, and was ultimately killed by them. That man, Maj. Charles Frost, became a hero in early New England.

“I maintain that there was only one Nicholas Frost and other historians have come to that conclusion, too,” Hart said. “The initial Frost had kind of a split personality, and it’s odd in that in the Frost family there was a lot of schizophrenia. I think he was a Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde character.”

The information is relevant, Hart said, because at the beginning of his career Frost wrote a long poem “Genealogical” in which he expressed disapproval of his famous New England ancestors and approval of their enemies — the Native Americans. And now there are two camps with substantially different views of Robert Frost.

“The Frost admirers still perpetuate the myth of Robert Frost as a very down-to-earth, healthy-minded, sane, kind, sort of grandfatherly character,” Hart said. “There are still a lot of people who want to believe that. Others say there’s a darker Frost that you can see in his poetry.”

John Cone and Hart spent time discussing schizophrenia and its impact on the Frost family. Cone’s mother, Irma — Robert Frost’s daughter — was schizophrenic. When she got older, Frost committed her to a mental hospital. The illness impacted other members of the family as well, such as Frost’s sister, who died in a mental hospital.

Frost's lowest romantic moment

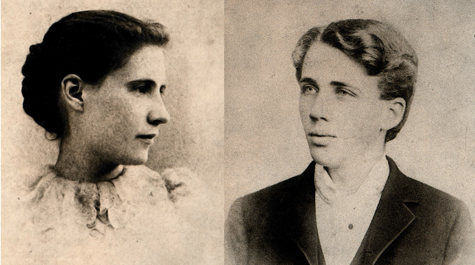

Hart delves deeply into an episode in Frost’s life that occurred in 1894, when he was 20. He desperately wanted to marry his high school girlfriend, Elinor White, pressuring her to quit St. Lawrence University as he had Dartmouth. She refused.

Frost calculated that the best way to win her over was to present her with a volume of his first poems. He put them together in a pamphlet, had them printed on fine paper and bound in leather with gold print. When he got to the front door of her boarding house in Canton, New York, Hart said, “She basically shut the door in his face.”

They ultimately married in 1895.

“He was devastated,” Hart said. “He always was extremely sensitive to any kind of rebuff or criticism.”

Frost boarded a steamship from New York to Norfolk, and walked into the Great Dismal Swamp where, Hart maintained, he planned to commit suicide in the woods by a canal. Some biographers have scoffed at the idea that Frost wanted to “throw… [his] life away” in the swamp.

“But that’s what he said when he was candid in interviews,” Hart said, “that he wanted to put an end to his life in the Great Dismal Swamp. He went in with his street clothes, a little satchel, no food or gear. He was rescued by a couple of guys in a boat who were going down the canal [to pick up some duck hunters].”

Hart said it was an episode Frost never forgot.

“One of the last poems he wrote was called ‘Kitty Hawk,’ and the first part was all about being rejected by Elinor and going to the Great Dismal Swamp ... I think he was like a devastated Romeo who was going to end his life.”

Hart doesn’t understand why other biographers seem averse to broaching the subject. He points to the fact that Frost’s son, Carol, committed suicide, that depression and schizophrenia ran through the family, and that some of Frost’s poems express a death-wish.

“A lot of biographers didn’t want to go into that subject,” Hart said, shrugging. “Maybe they thought they would turn away readers.”