Cate-Arries' book on Spanish Civil War refugees translated to Spanish

William & Mary Professor of Hispanic Studies Francie Cate-Arries recently returned from Spain and nearly two weeks of profound experiences presenting her book “Spanish Culture Behind Barbed Wire: Memory and Representation of the French Concentration Camps, 1939-1945.” (“Culturas del exilio español entre las alambradas: Literatura y memoria en Francia, 1939-1945.”)

The book originally appeared only in English when it was published in 2004. While there had been significant scholarship published on the Spanish Civil War and General Francisco Franco regime over decades, Cate-Arries’ book was the first monograph written about the literature and culture of the French internment camps for Spanish war refugees.

By the end of the Spanish Civil War in March 1939, nearly 500,000 Spaniards had fled the country to escape Franco’s military dictatorship. More than 275,000 of them found themselves interned in concentration camps in Southern France, exiles and outcasts in every sense of the word.

Although they were anti-fascists who expected a very different reception in democratic France, the French government was ill equipped to handle hundreds of thousands of war refugees. The French state also didn’t want to show friendship to the losers of a war whose adversaries had been very publicly supported by Hitler's Nazi Germany and Mussolini's Fascist Italy, to the point that France established diplomatic ties with Franco before the general even declared victory.

Book examines cultural, literary legacy of refugees

Cate-Arries’ book examines the cultural and literary legacy of the thousands of exiles who were interned in these concentration camps. She examined the literature and art that was produced, as well as refugees’ memories of the camps published during World War II, but never viewed or read within Spain during the Franco regime.

After the Franco dictatorship was dismantled in the late 1970s, there was a tacit understanding throughout the country that Spaniards were just going to move forward, not look back at this sad chapter of their history and wrestle with human rights violations and refugees.

Three years after Cate-Arries’ book was originally published, the Spanish Parliament modified this position in 2007 with its passage of complex -- and controversial -- legislation popularly known as the Law of Historical Memory, which opened the door for vigorous debate and coincided with new exhibits. In the case of Cataluña, museums were even opened, which focus on the history and cultural legacy of civil war exiles, including the inhabitants of those camps.

In March, an expanded version of Cate-Arries’ book was published in Spanish by Editorial Anthropos, a Barcelona publishing house, and in June she was invited to make presentations at four venues: the Museum of Catalonian History in Barcelona, the University of Barcelona, the Ateneo de Madrid in that city, and the Memorial Museum of Exile in La Junquera, right on the Spanish-French border, the 1939 gateway to exile for hundreds of thousands of war refugees.

There, her audience, whose questions to Cate-Arries were often in French, not Spanish, was almost entirely made up of the now-elderly children of exiles who crossed the border at that very spot, some of them babes in arms at the time. Most of them attended the lecture by way of Argelès in Southern France, once the site of the largest, most notorious internment camp, where their parents settled, often never to return to Spain.

They have formed a citizen’s group – FFREEE Association -- dedicated to keeping alive the legacy and memory of parents who fought and fled Franco in the name of democracy.

After the presentation, a man approached Cate-Arries and asked her to sign a book for his mother.

Emotional encounters with those who were there

“He said, ‘You know, my mother is 94 years old and she’s blind, and she’s not going to read this book,’” Cate-Arries recalled. “He said, ‘But I’m going to read it to her, and I’m going to read her the dedication that you write today. She was 21 years old when she went into that camp and that was a transformative moment in her life.’”

In the presentation at the Ateneo de Madrid, Cate-Arries shared the panel with Maria Luisa Libertad Fernández who was three weeks old when her parents carried her from Barcelona across the Spanish border, just before Franco's troops captured the city at the war’s end. She spent the first four years of her life interned in a series of French camps.

“I told her, ‘I wrote this book for you before I ever even met you,’” said Cate-Arries.

One question Cate-Arries heard continually was why she undertook this project. Did she also have relatives affected?

“Unlike many of the audience members who came to hear me speak, I have no familial ties to this chapter of Spanish history. The story I tell was taken from my study of published memoirs, novels, poetry, artwork and photography,” she said. “As an American, it was nice to join the ranks of others who have come to the story of Spain’s civil war as outsiders. In my case, I was captivated by the absolute poignant beauty of the stories of hope, solidarity, and humanity that emerged from these testimonies of camp veterans. We identify with them.”

The under-exposed work of Ione Robinson

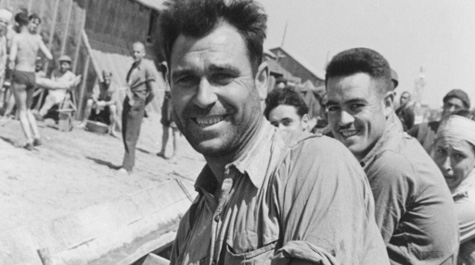

Among those left-leaning Americans who came to Spain to chronicle events during the war there was a little-known painter and photographer named Ione Robinson. She subsequently visited the concentration camps in France and began shooting photographs in May 1939, when the camps were just under construction.

Robinson’s grandson, C. J. Dallett, caught wind of Cate-Arries’ book in 2005 and contacted her with the information that he had saved his grandmother’s work and that she was welcome to incorporate it in her own.

“He had such a strong sense of the historical significance of these photographs and of his grandmother's legacy,” Cate-Arries explained. “His promise before her death in 1989 to honor that legacy was fulfilled in a 2002 New York show he curated. But he wanted assistance in disseminating her work in Spain itself."

At the time, Robinson’s photos of the camps were completely unknown in Spain, although months after she shot them, they did appear in the U.S. in a small spread in Life magazine. Cate-Arries took pains to ensure that the photos now included in the Spanish-language book would reach a wider audience in the home country of the exiles whom Robinson had captured with her camera.

Spain's war was the watershed mark for Robinson, like so many of her generation.

“She was born in 1910, and so was a young woman during the 1930s when Spain’s war began. She was very strongly involved with that group of New York intellectuals, artists and writers who were part of the American Left fighting for issues of equality and social justice in this country. And a lot of the issues over there reminded them of what was happening here.”

Robinson focused primarily on two groups of people the Life spread ignored: orphans and young, strong, virile men who didn’t fit the stereotype of concentration-camp exile.

“In the case of the men, she was taking these photos to try and help Spanish officials in exile make a case to other countries for immigration, especially Mexico, which eventually received more than 25,000 refugees,” she said. “She wanted those photos to say ‘our refugees are hard-working, healthy and ready to hit the ground running.”

Cate-Arries said that even after all these years, there is enormous interest and passion on the part of many Spaniards for the time of the war and exile of 1939, and especially among those whose families lost the war.

“One reason they feel so passionately about recovering the traumatic history of that time is because they want it to be officially recognized,” she said. “It’s not ‘The Exile Story,’ not ‘The Other Half’s Story.’ It’s the national story; it fills in the gaps of a nation’s history, and reminds the citizens of today's Spain that the struggle for democracy was waged decades earlier by the defenders of the Spanish Republic, behind barbed wire and beyond.”